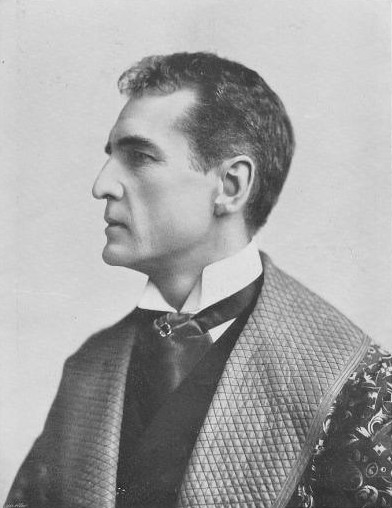

William Gillette

|

In her biography of the great French tragedian

Rachel, Rachel

Brownstein wrote this about the stars of the theater: "Stars are made up of

fictions; we acknowledge this when we call them fabulous, legendary. Images as

well as actual persons, they seem more and less real than the rest of us, and

therefore suggest that personal identity is bound up in illusions,

stereotypes, social and literary conventions." Peter Clark MacFarlane wrote in 1915 that William Gillette "has chosen to make a mystery of his existence off the stage. Nobody knows him, nobody sees him. His private character is less known than that of any other man in public life in America. People who have tried to see and know him have failed, will tell you he is cold, peculiar, taciturn, reserved, secretive, cynical, a recluse whose only intimates are cats. "Off the stage Gillette hoards his personality like a miser. On the stage he spends it like a prince. His plays and his characterization are his message to the public. The rest is silence. On the stage he is not a puppet, but a person. He wears a mask, but it is one of his own. He plays a part, but it is a part of himself, and himself is queer ~ truth to tell, odd, eccentric; no, all of these adjectives are too strong. ‘Himself’ is markedly individualistic." |

Like so many in his profession, Gillette fashioned a career out of

fictions. In another time and another place ~ let’s say, Elizabethan England ~

he would have performed in what were called masques, dramatic entertainments

designed for special occasions or holidays, or to amuse royalty. In these

little snippets of shows the performers sang, danced, read poetry, and

portrayed characters allegorical, mythological or classical. Spectacle being

all important, they wore elaborate costumes amidst minimal settings, and ~ for

good measure ~ they wore masks.

Gillette’s stage fictions were many: from Benvolio, Shylock and

Rosencrantz to Joe McCosh, Augustus Billings, Lewis Dumont, Crichton,

Carrington, Dearth, and Sherlock Holmes. These were the masks he wore on

stage. Off stage, the mask he wore was simpler but more impenetrable ~ aloof,

mysterious, eccentric, unknown and for the most part unknowable.

A master of reticence, he kept no journal, granted rare interviews,

and allowed only a privileged few inside his carefully constructed and

studiously maintained reserve. He burned most of his personal papers and

correspondence before his death. He wished most of all that no one would ever

know his secrets.

He made his living and his fortune in the most public of professions,

he was among the very best of his time at what he did, and he left an impact

still felt and acknowledged throughout the Western World nearly a century

after his death. Yet, his life remains a greater mystery than any presented on

the stage. Few knew him then. None know him now. Like the detective whose

image he created, he remains, in the words of Orson Welles, one of those

permanent profiles, everlasting silhouettes on the edge of the world. And,

there he stands, still invisible behind the mask he never removed, still known

mainly through the modern day masques he created for our entertainment.

So, just who and what was this permanent silhouette?

He invented or developed several aspects of modern theater. He helped

boost the careers of some of our most distinguished thespians. He built one of

the most eccentric homes in America. And he singlehandedly created the public

image of Sherlock Holmes.

He was born William Hooker Gillette ~ "Will" to his family and friends

~ in 1853 amidst the most cultured and intellectual haven in America. He

became a towering figure in an age of towering figures, a celebrity beyond the

scope of all but two of the neighbors of his youth. He grew up within shouting

distance of the lot on the western edge of Hartford, Connecticut, where Samuel

Clemens built his beautiful house and enjoyed his happiest and most productive

years; and he lived to be a featured speaker at the centennial celebration of

the great humorist's birth.

Gillette is best-known today as the living personification of Sherlock

Holmes. Over the years, he gave living substance to this fictional hero,

lifting him off the printed page and infusing into the character a life that

would never end. If Doyle gave Holmes to the world, it was Gillette who made

him seem so real that even today many people believe he actually lived. Georg

Schuttler, in his PhD thesis, William Gillette, Actor and Director

(University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1975), noted that By his striking

appearance, his economy of movement, and by his voice which concealed his

emotions, Gillette imparted complete realism to Sherlock Holmes. His portrayal

erased – at least for the three hours of the performance – all doubts that

such a master sleuth actually existed.

This Yankee aristocrat also established for all time the Holmes image

with the three items most associated with the master sleuth: the deerstalker

cap and the calabash pipe, thus creating arguably the most instantly

recognizable image in the world. And it was from Gillette's Holmes, not

Doyle's, that Hollywood film-makers derived four of the most famous words ever

spoken in the English language, "Elementary, my dear Watson."

But William Gillette (he never used his middle name or initial) was

more than simply the actor who gave Sherlock Holmes to the world. He was one

of the world's premier actors and playwrights before and after the turn of the

last century, a matinee idol of enormous appeal, and an imaginative genius who

made some important contributions to the theater that are still in use today.

He was to the theater what Clemens and Theodore Dreiser were to

American literature, a leading exponent of naturalism. Born in the era of

melodrama, with its grand gestures and sonorous declamations, he created in

his plays characters who talked and acted the way people talk and act in real

life. Held by the Enemy, his first Civil War drama, was a major step

toward modern theater in that it abandoned many of the crude devices of

nineteenth century melodrama and introduced realism into the sets, costumes,

props and sound effects. In Sherlock Holmes, he introduced the fade-in

at the beginning of each scene, and the fade-out at the end, instead of the

slam-bang finishes audiences were accustomed to. Clarice in 1905 was

significant because, for the first time, he sought to achieve dramatic action

through character rather than through situation and incident.

In a 63-year career, he established the strong, triumphant heroic

persona later employed on screen by John Wayne, Sean Connery and Harrison

Ford. And, along with fellow thespians John Drew, Otis Skinner, Henry Miller,

and a few others, he helped overcome America's puritanical objection to the

theater and showed that, while former actors may not have always been

gentlemen, there was no reason why a gentleman could not be an actor.

| There

are so many errors contained in the various written accounts of

Gillette's life that it is important to set these errors straight. One

may read ~ in magazine articles, books on the theater, and modern-day

internet websites ~ about his undergraduate education at some of our

leading universities, including Harvard and MIT; or that his family

disinherited him when he became an actor; or that his servant, Ozaki

Yukitaka, was ashamed of his lowly position when his famous brother, the

mayor of Tokyo, visited Hadlyme, and that Gillette and Ozaki exchanged

positions as master and servant for the famous brother's visit. Even his

age and the year of his birth are mostly listed wrong. None of this is

correct, but the public has no way of knowing the difference. In one sense, Gillette's story is not as appealing to modern readers because his was a life remarkably free of scandal. There were no paternity suits like the one that put Charles Chaplin in the 1940's headlines; no underage lovers like the girl with whom Errol Flynn cavorted; no casting couch or pornography collection like David Belasco's; not even a multitude of wives. His one marriage, while it lasted, was an idyllic romance, and his heartbreak at his wife’s death helped to disable him for half a decade. His colleagues later considered him to be quite the ladies man, and a succession of leading women was believed to have shared with him more than their dramatic talents; but this was no more unusual then than it is today; and, if the stories are true, at least he was discreet about it. |

|

He was charmed by children, particularly young girls like

nine-year-old child star Elsie Leslie, and by such young ladies as 17-year-old

Ethel Barrymore and 18-year-old Helen Hayes (with Gillette in 1918, right);

but his interest in them was purely paternal, and his conduct, however lavish

at times, was never inappropriate. Except for the reticent Ethel, whose vanity

he wounded with a bit too much gallantry, these young girls spoke glowingly of

him for as long as they lived.

He rarely drank alcohol and smoked more on stage than off, never

indulged in drugs, and overall lived a remarkably clean life. As a subject for

psychoanalyzing, this eccentric genius might make for a remarkable study, but

scandalmongers will have to look elsewhere for their fodder.

William Gillette, America's

Sherlock Holmes is one of the few authentic

accounts of his life, and it corrects many errors and misconceptions. Yet, in

the end, when it comes to piecing together a life many decades after it has

been lived, we are drawn back to the words of Gillette’s good friend, Samuel

Clemens, who claimed to have made a discovery of "the wide difference in

interest between ‘news’ and ‘history’; that news is history in its first and

best form, its vivid and fascinating form, and that history is the pale and

tranquil reflection of it."

For the better part of a century, William Gillette made news, much of

it known throughout the western world. Today, all we can offer is a pale and

tranquil reflection of it, gathered as best we can from news clippings and

letters and the published recollections of those who knew him and shared the

news he made.

Considering that, however, those pale and tranquil reflections give us

perhaps the greatest clue to how magnificent he really was, for the range of

his friends and acquaintances was enormous. First, the people he grew up

amongst in the intellectual and literary haven of Nook Farm, two of whom ~

Harriet Beecher Stowe and Samuel Clemens (Mark Twain) ~ did as much as, or

more than, all but a handful of others in shaping the century in which they

lived. He performed with America’s greatest actor of the century, Edwin Booth;

he was personally invited to become the first American actor to take the stage

owned by the greatest British actor of the era, Sir Henry Irving; and he was

managed by the world’s foremost theatrical genius, Charles Frohman.

He gave

initial boosts to the careers of four of our most cherished thespians: Maude

Adams, Ethel Barrymore, Charlie Chaplin, and Helen Hayes. And he was the

author’s personal choice for major roles in two plays by James M. Barrie, the

creator of Peter Pan. He dined with Presidents. He entertained kings and

queens. The political cartoonist Thomas Nast, the theatrical critic Alexander

Woollcott, Utah wartime governor and doctor/dentist/lawyer/wheeler-dealer

Frank Fuller, and the creator of literature’s best-known fictional hero, Sir

Arthur Conan Doyle, were his friends. As for admirers, simply create a Who’s

Who of the Western World for the last three decades of the nineteenth century

and the first three decades of the twentieth, and you’ll pretty much have

them.

His many other friends and admirers cover a broad landscape of the

international scene. They were enormously different, extraordinarily gifted

and brilliant, and possessed both a rare vitality and an immense sense of

purpose that shaped the times in which they lived. It is they ~ probably more

than anything in particular that Gillette ever accomplished ~ that made for

what was, after all, a very extraordinary life.

But, more than any play he ever wrote or acted in, William Gillette's

masterpiece was his retirement home, what the Washington Post called

the acme of his dreams, which ironically he never referred to as a castle,

although his neighbors often did. He once called it his "Hadlyme stone heap.

Others called it the rock pile or Gillette's folly."

Today, it is known around the world simply as Gillette Castle, and to

this day it summarizes the success upon which all his dreams were built,

dreams that turned his picturesque estate into a small boy’s dream of

paradise. He called his new monstrosity Seventh Sister, because the hill on

which it sits is the last of seven hills long referred to as the Seven

Sisters. Every inch, every corner, every crevice, every device, and every

accoutrement, was built according to his own design, including the outer

fieldstone walls, the crenelated towers, the entire floor plan, the interior

doors with their complex latches, and the special built-in furniture. It was

built of local fieldstone and cement, with an interior of southern white oak,

a wood so pure it has no knotholes in it and so durable it has withstood

nearly a century of wear. The castle contains 24 rooms and occupies about

14,000 square feet. The castle contains several mazes, hidden rooms and

passageways. There are 47 hand-carved doors, each unique in its design and

each with its own unique latch devised by the puzzle-loving dramatist. The

door latches, light switches, bolts and window fastenings took a local

carpenter an entire year to construct. The light switches are among the most

unique parts of the castle: some are fashioned after backstage theater levers,

others like steam locomotive levers.

The walls, of solid native granite, are five feet thick at the base

and taper to a thickness of two feet at the tower. The entire castle is

steel-framed but covered with either native field stone or the southern white

oak. The interior walls were covered with Javanese raffia matting, the only

imported thing in the castle, which was once very colorful but had faded

through the years; it was refurbished during the recent renovation. The mortar

holding the stones together, however, while white everywhere else, is colored

burgundy inside to add to the colorful decor.

Gillette Castle still sits majestically at the edge of the cliff two

hundred feet above the Connecticut River. It commands a broad panoramic view

of the river and the surrounding countryside, a view that is particularly

spectacular in the fall. A state park today, four miles south of East Haddam,

the castle is open to the public from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. daily from

Memorial Day to Columbus Day. Along with numerous newspaper and magazine

articles over the years, it was featured in National Geographic's Guide to

America's Great Houses (1999). Each year, the castle draws more than

100,000 visitors, to whom it stands as a testimony and a monument to the man

who built it. Henry A. Perkins concluded, "This ‘Castle’ is a tangible

expression of that personality, winning, whimsical, aloof, and will long stand

as his most perfect memorial when his plays and his rôles in them have been

forgotten."

At his Hadlyme castle estate, Gillette entertained many friends, the

most illustrious of them being President Calvin Coolidge, physicist Albert

Einstein, and Tokyo Mayor Ozaki Yukio, whose 1912 gift of the Japanese cherry

blossoms still beautifies the nation’s Capitol; and they all took a ride on

his miniature railroad.

Few names in the pantheon of dramatic artists are as illustrious as

his. Yet so many from his era are unknown today because they didn’t do what it

took to be remembered. What does it take? "For any actor to achieve some

measure of immortality", George Rowell observed, "he must have won success in a

‘classic’ role."

A few ~ a very few ~ achieve longer lasting fame, not just because of

their talents, but because they were blessed with a particular role, a

particular stage or film vehicle that would always be talked about long after

they were gone: Charlie Chaplin as the Little Tramp; Clark Gable as Rhett

Butler in Gone With the Wind; Errol Flynn as dashing boxer James J.

Corbett in Gentleman Jim; Frank Sinatra as the skinny, luckless Private

Maggio in From Here to Eternity; Barbra Streisand as New York-born

Fanny Brice in Funny Girl; Sean Connery as Agent 007; and Harrison Ford

in the Indiana Jones trilogy.

Certainly, Sherlock Holmes was the role Gillette was born to play, and

it is because he played it that his name is known today. The binding of the

actor to the role is one of those historical happenings that border on the

miraculous. There was simply no other actor at that time who could have done

with the character what he did; and, as Holmes aficionados are well aware,

the great detective is the most satisfying character in all the world’s

literature. It is a character to make a man immortal, and that was what it did

for Gillette.

Helen Hayes admitted, "I've admired other people in the role because

it's such a good play, but William Gillette is the only real Sherlock Holmes

for me, or for anyone else whoever saw him, I'm sure."

Walter Prichard Eaton wrote that "nobody who ever saw him as Sherlock

Holmes will think of him first in any role but that. The impersonation was one

of those rare and unforgettable marriages between a player and his part which

occur but seldom in a generation, and are always enshrined in theatrical

history."

And Vincent Starrett concluded,

"There can be little doubt that the

play also settled for all time the popular reputation of Mr. Gillette. Famous

as was his Secret Service and delightful as are contemporary memories

of his appearance in, say, The Admirable Crichton and Dear Brutus,

it is as the living embodiment of Sherlock Holmes that he will go down the

happy boulevards of time. It is not a bad fate."

Gillette was so divinely suited to the role that Doyle once told him

his only complaint was "that you made the poor hero of the anaemic printed

page a very limp object as compared with the glamour of your own personality

which you infuse into his stage presentment."

And Booth Tarkington paid him the most lyrical and heart-felt

compliment ever given to an artist: "I would rather see you play Sherlock

Holmes than be a child again on Christmas morning."

In appearance, personality, and acting ability, Gillette remains for

many to this day and for all time the definitive Sherlock Holmes.

Unpublished work © 2006 Henry Zecher