Sherlock Holmes and the 21st Century

[Three-part series published in The Pipe Smoker's Ephemeris in

1997-98]

Being a Reprint from the Reminiscences of

Henry Zecher, through the courtesy of John H. Watson, M.D., late of the Army

Medical Department, through the kind auspices of Dr. Watson's literary agent,

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, M.D., who gave to the world the two most famous

characters in all literature.

* * * * *

"Dr. Watson, Mr. Sherlock Holmes."

With these words, on New Year's Day 1881, in the chemical laboratory

at St. Bartholomew’s, the oldest hospital in England, young Stamford

introduced the two most famous characters in fiction. A bronze plaque on the

laboratory wall now commemorates the occasion.

Sherlock Holmes! The very name fires the imagination: Gas-lit London!

Fog rolling in off the Thames! The clip-clip-clop of horses' hoofs on

cobblestone streets!

The Red-Headed League! The Hound of the Baskervilles! The Six

Napoleons! The Valley of Fear! The Speckled Band!

Irene Adler, The Woman! Professor Moriarty, the Napoleon of

Crime! Scotland yard! Inspectors Gregson, Jones, MacDonald and Lestrade! Mrs.

Hudson! Watson! Baker Street!

The deerstalker cap! The Inverness cape! The magnifying lens! The

ever-present pipe!

These images, and many more, are as much a part of the Holmes mystique

as his deductions and his triumphs. They are, in fact, the very accoutrements

of what Vincent Starrett called "that little chamber of the heart: that

nostalgic country of the mind: where it is always 1895."

And yet it would seem today that Sherlock Holmes has become a thing of

the past. Holmes films do not go over well with modern theater goers because

audiences today have more perverse tastes and shorter attention spans.

Hollywood caters to this in a variety of ways, from the flesh, flash and

gadgetry of James Bond to the graphic violence and vulgar language of the

Die Hard and Lethal Weapon films. Unlike Double-O-Seven, Holmes is

not a ladies man; and, even though Watson most certainly is, Watson's

consorts are fully clothed. Holmes stories rely on skill and intellect, subtle

reasoning, non-too-obvious clues, and slow plot and character development, for

which modern audiences have little patience.

How well Holmes appears to fit into our modern world was reflected

rather pessimistically by Basil Rathbone (right) in his 1962 memoirs, In

and Out of Character: With the development in talking pictures of a mass

production of murder-mystery-sleuth-horror movies our audiences have been

delighted and amused by the extravagant shock technique employed...

In the early years of the present century theater audiences were

chilled to the marrow by William Gillette’s famous portrayal of Sherlock

Holmes, in a play I have read and been invited to revive. This play, believe

me, is so ludicrously funny today that the only possible way to present it in

the sixties would be to play it like The Drunkard, with Groucho Marx as

Sherlock Holmes. Time marches on!... Modern audiences would laugh this play

off the stage. Even the witticisms of Oscar Wilde are already somewhat dated,

and Mr. Shaw, despite his protestations, stands trembling on the brink! Only

Mr. Shakespeare remains as modern to us as he was to audiences in the year

1600. ‘Dated,’ that’s the word. The Sherlock Holmes stories are dated and

their pattern and style, generally speaking, unacceptable to an age where

science has proven that science fiction is another outdated joke (and turning

out to be a most unpleasant one). The only possible medium still available to

an acceptable present-day presentation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s stories

would be a full-length Disney cartoon.

The Holmes stories were first written in an age when literature was

both fully developed and a major form of entertainment. Books relied on the

reader's imagination to conjure up mental images of the scenes and the actions

of the characters. They required the reader to think. Radio would do

this to some degree once the electronic age came along, but radio was

nevertheless a more passive form of entertainment. We simply sat there and let

it perform. Of course, we had to imagine the scenes and characters; but plot,

dialogue and the sounds of action were all provided for us with no effort on

our part. It was television which became the ultimate catalyst in our

transformation from an active to a passive audience. It was the ultimate total

entertainment package, providing both sight and sound. In the process it also

anesthetized our imaginations and stunted our ability to think.

Rather than take part in the reasoning process, rather than being

mentally absorbed in the gradually evolving story with slowly developing

characters, we just sit back and let the tube entertain us. Life's plots and

problems are all resolved within a half-hour or an hour. And this

dysfunctional passivity has spilled over into such areas as our churches,

where a younger generation comes to church on Sunday morning, demands to be

entertained, and then goes home to remain uninvolved until the following

Sunday. It has also crippled many members of the young work force because they

lack the ability to reason forward and to act upon their reasoning. Told by a

supervisor to proceed through steps A and B, steps which will automatically

lead to step C, the thinking employee might well proceed and accomplish step C

and thus conclude the project; but too many young workers will do steps A and

B precisely as instructed, but will leave step C undone because they were not

specifically told to proceed.

Cable television has broadened our entertainment reach by providing us

access to things we would ordinarily leave our homes to see: concerts,

theater, sports and other activities. Through the magic of C-Span we can watch

our government in action and even watch our armies being sent into battle.

Said one college student on the first night of Desert Storm, "I'm going to pop

some popcorn and go watch the war."

We’ve lost our ability to communicate. Families gather in front of the

television set after dinner (or even during dinner), and never have to

actually converse. One of the big trends of the last 15 years has been what

the Washington Post Magazine once called "cocooning," the tendency of

couples to order fast food, rent a video, and stay at home each night instead

of becoming involved with their neighbors. Ours is an age of convenience and

seclusion from the most important elements of life: friendships, community

involvement, and the ability (not to mention the one-time necessity) of

reaching out beyond ourselves.

Finally, morals and ethics are disintegrating rapidly. From the idea

of we and striving for the common good, we are now in the age of me and the

gratification of our own petty complaints and selfish personal desires, no

matter at whose expense the gratification comes. War and white-collar crime

have grown and spread as fast as the technology that makes them possible.

Politicians, businessmen, and leaders at all levels of society are blatantly

serving their own or supportive special interests rather than working for the

overall common good.

Therefore, for many of us, Holmes is a breath of fresh air, a

throw-back to a simpler age when standards and morals were black and white,

and rarely gray; when good was right and evil was plainly evil; when people

actually communicated and reached out to each other; and when country and

honor meant something more than mere entries in the history books which too

many students never read anyway.

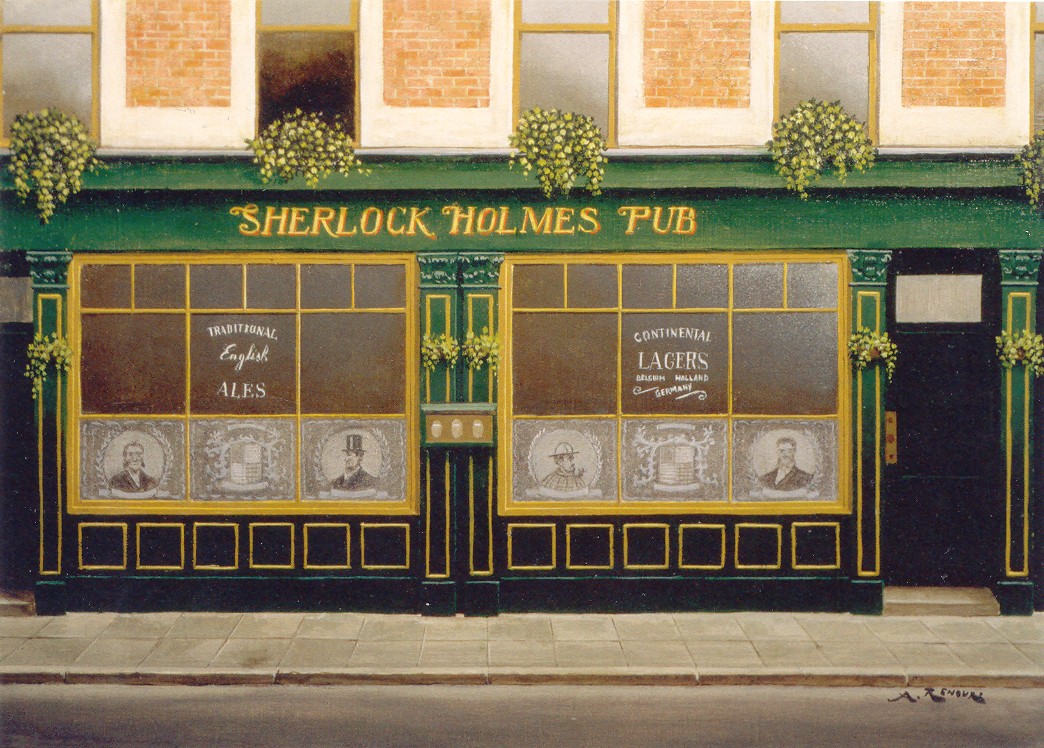

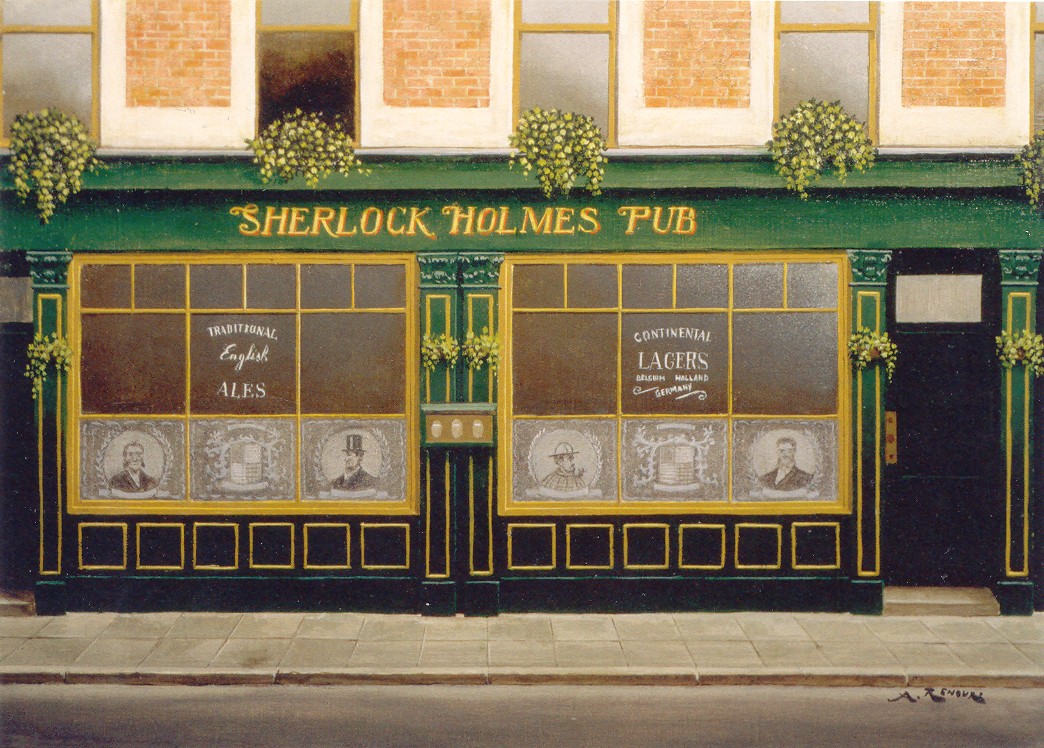

Fortunately, there are more than just the stories to fill the void.

Holmes’ life has been chronicled, and his world recreated, for all to enjoy.

The sitting room Holmes and Watson shared at 221B Baker Street (history's most

famous address, never truly identified) has been reassembled in a number of

places, most notably the Sherlock Holmes Pub (right), once the Northumberland

Hotel, where one of Sir Henry Baskerville's boots disappeared. There is also a

Sherlock Holmes Hotel on Baker Street, and the Sherlock Holmes Museum, which

recreates at 221 Baker Street the entire suite Holmes and Watson would have

lived in had they really lived.

The detective's image, picture, or silhouette is everywhere. And

London itself still retains some of the old flavor because many shops serve a

conservative clientele and shopkeepers are therefore not willing to modernize

their store-fronts, which appear much as they did before the Great War. So

many of Holmes' old haunts are still there, many of them unchanged from a

century ago when the master sleuth walked the streets of London with Watson at

his side:

* Pall

Mall, where he and brother Mycroft lounged at the Diogenes Club;

* Simpson's on

the Strand, where Holmes and Watson dined;

* The British Museum, where Holmes studied;

* Covent

Garden, where Holmes visited a dealer in geese searching for the man who

stole the Blue Carbuncle;

* Pope's Court, off Fleet Street, site of the headquarters of the

Red-Headed League;

* Charing Cross, from which station Irene Adler made her escape,

and to which hospital Holmes was taken after he was brutally assaulted

outside the Royal Cafe;

* Bow Street,

where the man with the twisted lip begged;

* The

theaters he attended: the Lyceum, the Haymarket, Covent Garden, Albert

Hall;

* The railroad stations: Baker Street, Victoria, Charing Cross,

Waterloo;

* The river Thames, up which Holmes and Watson chased Jonathan

Small in pursuit of the Agra treasure;

* Lloyd's Bank at Pall Mall, with Cox & Company still printed on

the door, keepers of that battered old tin dispatch box with John H.

Watson, M.D., printed on the lid, in which Watson told us he left so many

as yet unrecounted adventures for which the world was not yet prepared;

* And, finally, Baker Street, once at the outskirts but now near

the very center of London, and still the most famous and romantic

thoroughfare in the world.

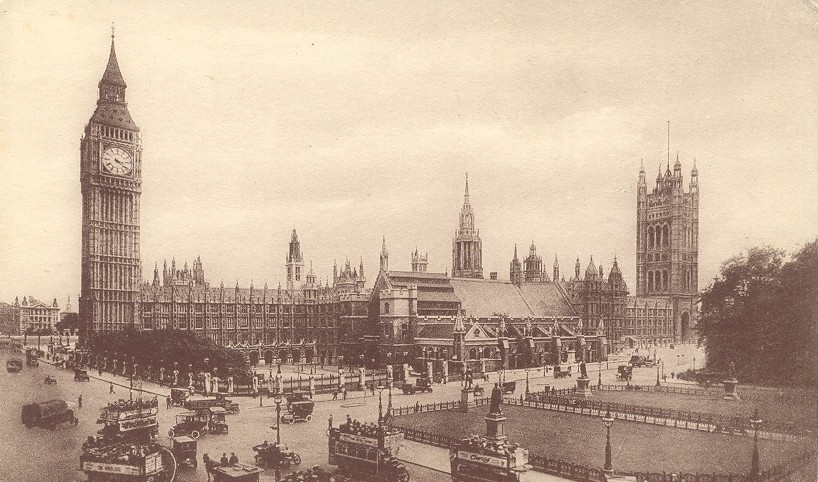

London is more than Westminster Abbey, Big Ben, and the Thames; and it

is more than simply the old capital of history's greatest empire on which the

sun never set. It is the capital of the realm of our imagination, of a

romantic era long since past. There are many famous boulevards around the

world: Broadway in New York City, the Champs Elysees in Paris, the Street of

David in Jerusalem, the Bubbling Well Road in Shanghai, the Ghat of the Ganges

in Benares; but none receive the number of visitors, or are known so

intimately around the world, as London's Baker Street, the home of Sherlock

Holmes.

Anyone wishing to go there can trace Holmes' steps with the help of

Michael Harrison’s wonderful views of Holmes' London, and the places he went,

in The London of Sherlock Holmes and In the Footsteps of Sherlock

Holmes.

Tsukasa Kobayashi, Akane Higashiyama and Masaharu Uemura published

"then and now" photographs of these sites, as well as other valuable

information, in Sherlock Holmes's London.

The Sherlock Holmes Society of London, provides valuable information

as well, including a brochure on Holmesian London.

Several guide books are helpful, but Oscar Wilde's London is

particularly so because it divides the city into 10 sections for walking

tours, with descriptions of the sites to be seen there. Of course, pipe shops

are an obvious place to search for Holmes memorabilia, as well as capturing

the true flavor of the man, and Michael Butler of The Pipesmokers' Council in

London provides a most helpful directory of London tobacco shops, along with

directions. Other guide books cover Holmes sites in London, around the British

Isles and on continental Europe, and articles covering tours and tour sites

have appeared over the years in The Sherlock Holmes Journal.

The Creation of Sherlock Holmes

We know of Holmes, of course, because of his biographer (his

"Boswell," he called him): John H. Watson, M.D., who had already seen all the

adventure he would ever want to see, and was quite prepared for the sedentary

life of a medical practitioner when he chanced upon young Stamford at the

Criterion Bar that New Year's Day in 1881. Watson was subsequently introduced

to the man he would serve as biographer, helper, companion and friend for more

than two decades, and whose accounts of Holmes' cases would make the London

detective renowned around the world.

Holmes' career as the world's first consultive detective lasted from

1877 until 1903. In that time he would have encountered most of the famous

characters of the era: from Theodore Roosevelt, Sigmund Freud, George Bernard

Shaw, Alfred Dreyfus, Aleister Crowley and Jack the Ripper, to Count Dracula,

Dr. Fu Manchu, Lord Greystoke (Tarzan), Mr. Hyde and the Phantom of the Opera.

In one book or another, he has met these and many more.

The Ripper murders of five prostitutes in Whitechapel have

particularly beguiled our imaginations because of their savagery and because

the Ripper was never identified, in spite of Holmes' efforts to catch him in

several novels and two feature films. You may take the "Jack the Ripper Tour"

of Whitechapel, where all five victims were butchered. It is given at night,

and is not for the squeamish or the faint of heart.

Yet, ironically, Jack the Ripper ~ who was very real ~ was greatly

responsible for the fictional Holmes' early popularity. The first Holmes

adventure, A Study In Scarlet, appeared in book form in 1888 just as

the Whitechapel murders were terrorizing Britain, and Holmes represented an

unheard-of high degree of detective sophistication which Scotland Yard had not

yet attained. Charles Higham revealed in The Adventures of Conan Doyle,

"Magazine after magazine, newspaper after newspaper, cried out for just the

kind of deductive genius which Holmes, in fiction, embodied. The failure of

the police to solve the puzzle of the Ripper murders only accentuated a

psychological need for a Holmesian hero. If the public could not find him in

life, they would find him in books, and find him they did."

The creation of Sherlock Holmes must rank as one of the truly great

accomplishments of all time. To begin with, he was a composite character.

Putting pen to paper in 1885, Doyle (right) recalled his Edinburgh professor,

Joseph Bell, M.D., F.R.C.S., consulting surgeon to the Royal Infirmary and

Royal Hospital for Sick Children, and Member of University Court, Edinburgh

University. Dr. Bell could deduce a man's habits, his trade, his nationality,

his mere appearance and his place of origin, by subtle observations. "Use your

eyes, sir!" he would tell a student observing a patient. "Use your ears, use

your brain, your bump of perception, and use your powers of deduction."

When a soldier entered his room, Bell observed, "Ah, you are a

soldier, and a non-commissioned officer at that. You have served in Bermuda.

Now how do I know that, gentlemen? Because he came into the room without even

taking his hat off, as he would go into an orderly room. He was a soldier. A

slight, authoritative air, combined with his age, shows that he was a

non-commissioned officer. A rash on his forehead tells me he was in Bermuda

and subject to a certain rash known only there."

Does this recall the retired Sergeant of Marines whom Holmes and

Watson saw approaching their door in A Study in Scarlet?

However, Bell's genius began and ended in the classroom, for he could

never use his powers to solve a single crime.

Also on Doyle's mind were Edgar Allan Poe's C. Auguste Dupin, the

energetic investigator; Emile Gaboriau's Monsieur Lecoq, with his neatly

dovetailing plots; and Wilkie Collins' Sergeant Cuff, the tall, beak-nosed,

cadaverous hunter. But Doyle also infused much of himself into his new

detective, plus one man more. Of all the men he had admired from his youth, he

most wanted to meet a Harvard medical professor and criminal psychologist who

was the author of many medical monographs as well as poetry ("Old Ironsides"

and the "Breakfast-Table" papers), and who would give to Doyle's creation both

his own investigative methods as well as his surname: Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Strangely, Dr. Watson, who was in contrast to Holmes, was also Doyle,

the Doyle the public knew: medical man, family man, British gentleman. Holmes

was that side of Doyle the public never saw: manic-depressive, active at odd

hours, packrat, and creative investigator.

"Holmes and Watson live side by side," Higham wrote, "like a married

couple ~ or the two opposing sides of Conan Doyle's own personality."

In creating his new detective, Doyle wanted more than mere

investigative energy, dove-tailing plots, or a relentless manhunter. Doyle's

detective had to do what no other had ever managed: he must reduce the

detection of crime to an exact science. This was easier said than done,

because at this time scientific crime detection was still in its infancy, as

demonstrated by Alphonse Bertillon's attempts in Paris to identify criminals

by measuring their bones. It was also marred by superstition, as in Cesare

Lombroso's claim in 1864 that some people were born criminals and that he

could identify any man as a criminal, and a specific type of criminal at that,

simply by observing his physical characteristics. France’s François Eugène

Vidocq, chef de la Sûreté in Paris, had made quite a name for himself as a

detective earlier in the century, and is believed to have been the inspiration

for Poe’s Dupin; but Vidocq was an exception to the general rule. Police

detectives by the 1880s were often little more than glorified Bobbies with

neither training in, nor understanding of, scientific crime detection.

Furthermore, Doyle was trying to enlarge upon the concept of the

detective formula put together by Poe: the locked room in which an apparently

impossible crime has been committed, a crime the detective ~ against all odds

~ sets out to solve with superior intellect, perception, and skill. Poe

perfected the detective story and the psychological thriller. Anna Katherine

Green, Mary Roberts Rinehart, Collins, and Gaboriau had followed this formula

with great success; but now Doyle sought to improve on even them. He had to

start with his heroes and then close his eyes to enlarge upon them, imagining

how he would go about it if he was the man capable of doing what he was trying

to do. From that imagination sprang the master sleuth of Baker Street.

How well Doyle succeeded is demonstrated by the fact that it was not

until the appearance of Hans Gross's Criminal Investigation that the

basis for modern crime detection and police systems came into being; yet Doyle

anticipated Gross. Among its many subjects, Gross's book featured a section on

tracing footprints and casting their impressions in plaster of Paris. Holmes

traced footprints in A Study In Scarlet (published in Beeton's

Christmas Annual for 1887) and referred to his monograph on tracing

footprints and casting their impressions in Plaster of Paris in The Sign of

Four (published in the United States in 1890).

"No man lives or has ever lived who has brought the same amount of

study and of natural talent to the detection of crime which I have done,"

Holmes lamented, and what he said was true. Criminal Investigation was

not published until 1891, by which time both England and America knew the name

of Sherlock Holmes.

In 1889 Joseph Marshall Stoddart of the American Lippincott's

Monthly Magazine brought Doyle and Oscar Wilde together for dinner at

London's Langham Hotel in order to commission from each a novel for his

magazine. Following a most charming evening, Wilde wrote The Picture of

Dorian Gray and Doyle produced The Sign of Four, which introduced

Holmes to a most receptive American audience. In 1891 the new and hugely

popular London magazine, The Strand, abandoned novels in favor of short

stories by celebrated authors, and the first of the Holmes short stories, "A

Scandal In Bohemia," appeared in the July issue, followed a month later by

"The Red-Headed League." In only two months, Sherlock Holmes became the most

talked-about figure in London and stood upon a world stage from which he would

never retreat.

In appearance, Holmes was modeled after Walter Paget, brother of

illustrator Sidney Paget, whose illustrations accompanied Doyle's stories in

The Strand. American illustrator Frederic Dorr Steele, who illustrated

29 of the 32 stories which appeared after Holmes returned from the Reichenbach

abyss, modeled Holmes after William Gillette, the great actor who introduced

Holmes to the American stage before the turn of the century.

It has been claimed that Paget modeled Watson after Doyle himself,

although they had not yet met; and Watson's description ~ thickset, bull-neck,

mustache ~ better fits Doyle's secretary of 40 years, Major Alfred Wood. There

is some confusion over the model for Watson. And, while Doyle had pictured

Holmes as being more like Sergeant Cuff (tall, cadaverous and ugly), Paget

made him sexually attractive and handsome, in other words, the man of the 90s.

"His image of Sherlock Holmes," Higham explained, "had hundreds of

thousands of young women yearn for this fictional character as they might

yearn for a stage actor, and a similar number of men wanted to emulate his

flawless tailoring and various forms of headgear. Sherlock Holmes became a

star before movies were born..." The height of Holmes mania occurred, of all

times, upon his "death" at the Reichenbach Falls in "The Final Problem,"

published in 1893. No fewer than 20,000 readers canceled their subscriptions

to The Strand and tens of thousands more wrote angry letters (one of

which began, "You beast...").

Men wore black bands on their hats and coat sleeves and some women

dressed in mourning. For may readers, it seemed like what one cartoonist

called Life’s darkest hour.

Doyle felt that Holmes kept him from tending to his wife, who was

dying from tuberculosis, and that Holmes interfered with his more worthy

literary efforts. As it turned out, Doyle later admitted that he would not

have written more had he not killed Holmes off, and ten years later he yielded

to the pressure and brought Holmes back, easy to do since "fortunately no

coroner had pronounced upon the remains." He was never to kill him again,

allowing him instead to continue his career and eventually to retire to his

villa at Fulworth, on the southern slope of the Sussex Downs, commanding a

wonderful view of the English Channel.

There, on the wind-swept slopes overlooking the Channel, Holmes kept

bees and wrote his memoirs, with only his old housekeeper to keep him company.

But it is at 221B Baker Street that he and Watson reside in the world of our

dreams, as real to us as we are to each other, these two men who never lived,

at an address that never existed, where, to fans of all ages around the world,

they remain to this day.

Holmes and Real Life Police

In an era before the development of scientific crime detection,

Sherlock Holmes made his presence known in the very precincts where it

mattered most.

He was the original scientific sleuth and, by the time he retired,

entire wings of police departments were devoted to the forensic and

pathological studies he once conducted alone at Baker Street. The stories

became required reading at many police academies; and, well into the 20th

century, Dr. Edmond Locard, head of the police laboratory at Lyons, wrote, "I

hold that a police expert, or an examining magistrate, would not find it a

waste of time to read Doyle's novels... If, in the police laboratory at Lyons,

we are interested in any unusual way in this problem of dust, it is because of

having absorbed ideas found in (Hans) Gross and Conan Doyle."

America's greatest living detective, William J. Burns, traveled to

London in 1912 and told Doyle that Holmes' methods were entirely practical;

and Doyle himself, that paladin of lost causes, flourishing what Robert Louis

Stevenson called "the white plume of Conan Doyle,

used Holmes's methods to solve crimes and undo gross miscarriages of justice.

Doyle, however, was an amateur, and he did such things only on

occasion. New Zealand's Sir Sydney Smith used Holmes's deductive and reasoning

methods for half a century as one of the world's leading experts in forensic

medicine. Smith received his medical training at Doyle's alma mater, Edinburgh

University, where Joseph Bell's colleague, Harvey Littlejohn, was his teacher.

Smith was also lecturer in forensic medicine at Edinburgh and the original

developer of ballistic forensics, which proved that bullets fired by the same

gun will have the same distinctive markings.

They called him the "real-life Sherlock Holmes," and there were

literally hundreds of cases in which he reasoned correctly from a small piece

of evidence. Here is just one: Handed a piece of leather about the size of a

fingernail (the only evidence from a safe-cracking), Smith subjected the

particle to a battery of tests ~ probing, x-rays, microscopic examination, and

chemical analysis. His pronouncement: "The leather is off a man's shoe, size 9

½. It is a black shoe, has been worn for about two years, was made in England

and the wearer had been walking through a lime-sprinkled field recently." They

caught the criminal that very day.

"Today, criminal investigation is a science," Smith recalled after his

retirement. "This was not always so, and the change owes much to the influence

of Sherlock Holmes. Conan Doyle had the rare, perhaps unique, distinction of

seeing life become true to his fiction."

Doyle revolutionized the detective story, which Edgar Allan Poe had

essentially created. Dorothy Sayers wrote, "Conan Doyle took up the Poe

formula and galvanized it into life and popularity. He cut out the elaborate

psychological introductions, or restated them in crisp dialogue. He brought

into prominence what Poe had only lightly touched upon ~ the deduction of

staggering conclusions from trifling indications in the Dumas-Cooper-Gaboriau

manner. He was sparkling, surprising, and short. It was the triumph of the

epigram.

While previous detective stories cast criminals strictly from the

lower classes of society, Doyle represented them as coming from the upper

classes as well, including the professional and the well-educated. "When a

doctor does go wrong, he is the first of criminals, Holmes told Watson in

The Speckled Band. He has nerve and he has knowledge."

One thing Doyle invented outright which few give him credit for is

what John Dickson Carr called "the enigmatic clue." This is a clue given right

up front for us to see and draw deductions from. It is underlined. It is

emphasized. It runs back through the story and regurgitates over and over: the

wedding ring in A Study In Scarlet, the missing dumbbell in The

Valley of Fear, the curious incident of the dog in the nighttime in

Silver Blaze. "The dog did nothing in the nighttime," Inspector Gregory

says, and Holmes responds, "That was the curious incident."

Gregory still doesn't get it; and neither, of course, does Watson.

Poor Watson. We pity him for being so dense. "Dear me, Watson," Holmes says,

"is it possible that you have not penetrated the fact that the case hangs upon

the missing dumbbell?" But we didn't see it either.

"Call this 'Sherlockismus'," Carr suggested, "call it any fancy name;

the fact remains that it is a clue, and a thundering good clue at that. It is

the trick by which the detective ~ while giving you perfectly fair opportunity

to guess ~ nevertheless makes you wonder what in sanity's name he is talking

about. The creator of Sherlock Holmes invented it; and nobody except the great

G. K. Chesterton, whose Father Brown stories were so deeply influenced by the

device, has ever done it half so well."

Page, Stage and Screen

Doyle was a master story-teller with an uncanny knack for writing in a

style which brought both his stories and his characters to life on the printed

page. Holmes thus sprang to life in four novels and 56 short stories ~ known

today as "the canon." Since then, many writers have given us pastiches,

serious novels and short stories in which Holmes has solved one mystery after

another, outwitted villains and arch-fiends, and saved western civilization

from disaster.

Others have gone into Sherlockian scholarship, producing studies of

elements from the stories and thereby enriching our knowledge and

understanding of Holmes and the world in which he lived. Among the foremost of

these scholars have been Chicago Tribune columnist Vincent Starrett,

whose book, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1933), was the first

great study of the entire Holmes phenomenon; Christopher Morley, founder of

the Baker Street Irregulars, who conducted many illustrative studies and wrote

introductions to many volumes of Holmes stories, including The Complete

Sherlock Holmes; and William S. Baring-Gould, whose chronological studies

greatly aided and enriched our study of the canon.

There are, of course, outrageous liberties taken. Some have gone too

far astray in their lust for the ever-fresh approach. For example, some have

suggested that Holmes was gay, and that he and Watson enjoyed a homosexual

relationship. A favorite avenue many take is to cast his "drug addiction" as

the cause of, say, an obsession with his boyhood mathematics professor as an

imaginary "Napoleon of Crime, the approach put forth in Nicholas Meyer's

The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, which was also made into a movie. Or his drug

addiction was made the source of his becoming Jack the Ripper (again, with no

real Moriarty) in Michael Dibdin's The Last Sherlock Holmes Story.

Theorizing where Doyle never went (i.e., explaining his misogyny by way of an

adulterous mother) is one thing; distorting basic facts is something else

entirely. Writers from Dorothy Sayers to Vincent Starrett warned against such

aberrant sensationalism, obviously to no avail.

Scholarship within the bounds of the canon, however, goes on. For

example, the evidence is strong that Holmes was either born or raised, or

spent much time, in America. This fueled the theory of the 32nd President of

the United States, himself a member of the Baker Street Irregulars. Franklin

D. Roosevelt suggested that Holmes had been American-born, a foundling raised

in the criminal underworld. "At an early age he felt the urge to do something

for mankind," FDR wrote. "He was too well known in top circles in this country

and, therefore, chose to operate in England. His attributes were primarily

American, not English." One can only wonder what Winston Churchill thought of

that!

Baring-Gould, as well as others, saw much evidence of a young adult

Holmes traveling through the United States before embarking on his

crime-fighting career.

Throughout the canon Holmes displays a keen knowledge of America, and

Baring-Gould speculated that Holmes had traveled through the states as part of

a theatrical troup in the years before beginning his career as a detective,

thus acquiring his knowledge of stage acting and the use of makeup and

disguise in particular, and of America itself in general. There is certainly

no question that Holmes held the United States in very high esteem.

Of the most widely-read Holmesian authors, three in particular stand

out, first and foremost being Baring-Gould, author of several chronological

studies of the canon, including a two-volume set, The Annotated Sherlock

Holmes. Among his many fine works, he wrote the definitive biography,

Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, A Life of the World's First Consulting

Detective, and contributed an article to Sports Illustrated

Magazine, May 27, 1963, "Sherlock Holmes, Sportsman." Baring-Gould revealed

Holmes to be an exceptional natural athlete with immense endurance, an

excellent boxer and swordsman, a crack shot, and a sound judge of horseflesh.

Nicholas Meyer, an outstanding novelist, screenwriter and film

director (including two of the Star Trek films), even after the

anathematic The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, has given us two splendid

accounts more in fitting with the traditional portrait: The West End Horror,

in which Holmes encounters George Bernard Shaw while investigating a bubonic

plague outbreak in London, and The Canary Trainer, in which Holmes goes

after the Phantom of the Opera.

The premier Holmesian author in recent years, however, has been

Michael Hardwick, a giant in English period fiction as well as the Holmes

saga, and a man who appeared to have a deep affinity for Dr. Watson. This

affinity enabled him to project the doctor's character better than any other

writer, past or present, after Doyle himself.

Hardwick dramatized many of Doyle's stories for television and the

stage. He adopted The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes from screenplay

to novel, and he is the only man yet to write (or "edit") biographies of all

three members of the triumpherate: Holmes (Sherlock Holmes: My Life and

Crimes), Watson (The Private Life of Dr. Watson), and Doyle's

relationship to Holmes (The Man Who Was Sherlock Holmes, co-authored

with wife Mollie). He was the first since Christopher Morley to receive from

the Baker Street Irregulars The Sign of the Four, one of the most prestigious

awards any Sherlockian can receive. He and Mollie, a successful mystery writer

in her own right, wrote companion works to the canon, as well as novelizations

of such TV series as Upstairs, Downstairs and The Duchess of Duke

Street, and such movies as The Man Who Would Be King and The

Four Musketeers. Hardwick, who died on March 4, 1991, wrote two

outstanding full-length Holmes patisches: Revenge of the Hound and

Prisoner of the Devil, the latter of which sent Holmes into the midst of

the internationally scandalous Dreyfus affair. Prisoner of the Devil is

considered by many Sherlockians to be the greatest Holmes mystery outside of

the canon. However, executors of the Conan Doyle estate forbade Hardwick

permission to write another Holmes novel, declaring they would rather that

readers read Doyle’s original stories instead. Considering Hardwick’s

faithfulness to the original, Holmesians around the world viewed this action

as both ungracious and ungrateful.

Of course, seeing and hearing Holmes and Watson is always thrilling,

and many actors have brought Doyle's creation to life on stage and screen

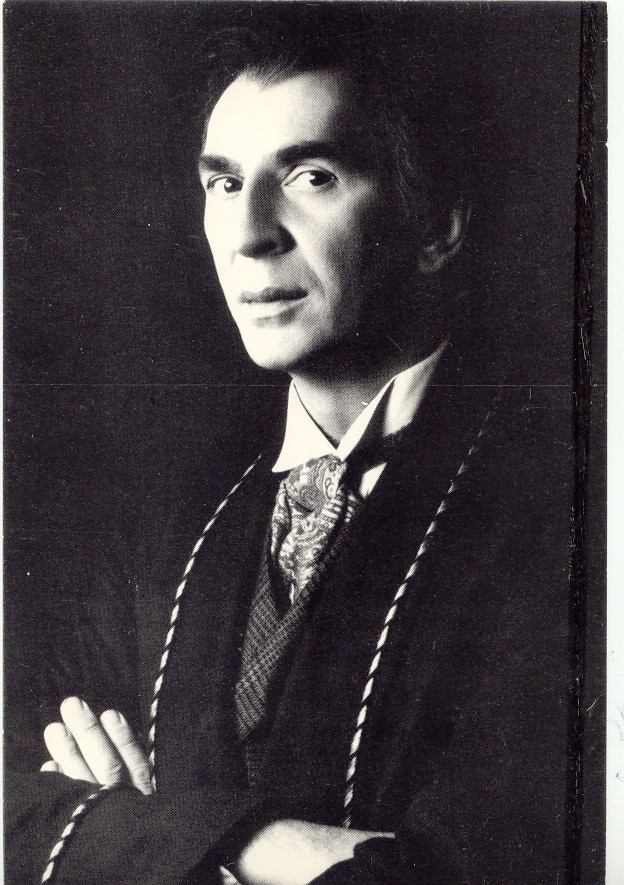

since the great American actor William Gillette (right) first portrayed Holmes

on the American stage in 1899. Gillette became permanently identified with the

role, as were Eille Norwood, Arthur Wontner and Basil Rathbone; however, like

Wontner, and unlike Rathbone, Gillette did not overly mind. Though he

sometimes tired of Holmes, he played the detective in the only movie he ever

made, Sherlock Holmes in 1916, and on stage periodically for the rest

of his life. In terms of personality, stage presence, and appearance, coupled

with tremendous acting ability, Gillette remains the definitive Holmes of all

time.

Radio, whose golden age was the 1930s and 40s, was a fertile field for

Holmes mysteries. Gillette was the first to play Holmes on radio, doing the

first broadcast in a 35-program series on WEAF-NBC on October 20, 1930;

Richard Gordon finished out this series and did several more. Rathbone,

Wontner, Orson Welles, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, and Sir John Gielgud also

portrayed Holmes on radio before, during and after the Second World War.

Television also brought Holmes to the air with Alan Wheatley

portraying Holmes for the BBC in 1951, and Ronald Howard, son of actor Leslie

Howard, portraying Holmes in 39 programs from 1953 to 1954. Rathbone played

Holmes in one episode of the 1953 CBS Suspense series, and remains

today the only actor to play Holmes on stage, radio, film, television and

phonograph records. Douglas Wilmer and Peter Cushing portrayed Holmes in

further BBC productions in the 1960s, and Jeremy Brett on PBS eventually

became the modern world’s most popular and authentic modern Holmes. Several

made for TV movies have also appeared in recent years.

Stage productions have flourished during and after Gillette's

lifetime, but new wrinkles have been introduced from time to time. In 1953

Margaret Dale and Richard Arnell produced a ballet, The Great Detective,

which did not go over well in spite of Kenneth Macmillan doing double duty as

both Holmes and Professor Moriarty; and in 1965 the musical Baker Street,

starring Fritz Weaver as a singing Holmes, debuted at the Broadway Theatre in

New York City.

They Might Be Giants, about an American judge who imagines he

is Sherlock Holmes, first appeared as a play at the Theatre Royal in

Stratford, London, in 1961, and later as a 1971 film starring George C. Scott;

neither did particularly well.

Gillette's original play, Sherlock Holmes, which he wrote

himself, has had a remarkable life of its own. It was the basis of both

Gillette's 1916 venture into film and John Barrymore's portrayal of Holmes in

1922's like-titled Sherlock Holmes, the most elaborately-staged Holmes

film up to that time. In 1974 the Royal Shakespeare Company revived it with

enormous success in London, Washington and New York with the role of Holmes

filled by John Wood in London and John Neville and Leonard Nimoy in the United

States. It was revived again in Williamstown in the 1980s with Frank Langella

(right) in the starring role, and was even taped and broadcast by Home Box

Office. This great success would appear to render Basil Rathbone’s pessimistic

views untenable, and it has been suggested that he was merely disgruntled over

the failure of his own ill-fated play, Sherlock Holmes, which was

written by his wife and ran in Boston but survived for only three performances

on Broadway in 1953 before closing down.

Nimoy, also known as Mr. Spock in the Star Trek television and

film series, is not the only member of the Enterprise crew to have a

connection with the detective. William Shatner (aka, Captain Kirk) portrayed

Stapleton in the 1972 television production of The Hound of the

Baskervilles, starring Stewart Granger as Holmes.

Jeremy Brett also portrayed Holmes on stage in the play The Secret

of Sherlock Holmes, which he commissioned from Jeremy Paul, who later

wrote some of the Granada scripts. He performed in London and the provinces

during a break from filming the Granada series and discussed bringing the play

to the United States, though he never did.

Of course, it is in the movie theaters that we have really relished

Holmes, and there have been many great actors who portrayed the detective on

film. The first Holmes film ever made, Sherlock Holmes Baffled in 1900,

was a 49-second short made for viewing in a peep-show machine. The robed

figure comes to find a burglar, who (through trick photography) disappears and

leaves Holmes baffled. It was an inauspicious beginning for the Holmes film

saga, but in 1906 a more serious effort, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes,

or Held for a Ransom, appeared in the United States. Films soon

appeared in America and Europe. Holmes films have been shown on movie and

television screens all around the world ever since. The Nordisk film company

in Denmark produced no fewer than 11 Holmes films between 1908 and 1911 alone.

Holmes’ Greatest Challenge

Sherlock Holmes’ greatest challenge may be his role in the oncoming

21st century. In this fast-paced electronic age of space exploration (both

real and fictional), world-wide computerization, and an ever-growing global

community, and with the over-indulgence in sex and action in modern films, it

would seem that Holmes and Watson would be as archaic and as antiquated as the gasogene, the gas lamp, and the horse-drawn buggy.

But are they?

Rest assured that ~ globalization and James Bond notwithstanding ~ the

detective and his Boswell are both alive and well. No matter how

technologically advanced we are, no matter how ecumenical and fast-paced

society becomes, there will always be room in people's hearts for Sherlock

Holmes and Dr. Watson.

Even before his creator's death, Holmes’ name had spread to every

corner of the globe. The canon has been translated into more than 60 languages

in nearly 1900 books and phamplets. There have been, since Doyle's death in

1930, thousands of writings about the writings, nearly 700 additional

mysteries and parodies, and more than 120 plays, ranking Holmes among the top

five most written-about characters of all time. And, according to the 1996

Guiness Book of World Records, Holmes is the most portrayed character on

film, with no fewer than 75 actors appearing as Holmes in 211 movies since his

peep machine debut in 1900. Furthermore, as Ron Haydock noted in The

History of Sherlock Holmes in Stage, Films, T.V. & Radio Since 1899

(Number 1, 1975), One of the all time great mystery classics, and easily the

most celebrated of all the Sherlock Holmes stories, The Hound of the

Baskervilles...claims the distinction of being filmed more times than any

other work of any other kind by any other writer. The actors starring in these

films have been Alwin Neuss, Bruno Guttner, Eilee Norwood, Basil Rathbone,

Carylyle Blackwell, Robert Rendell, Eugene Burge, Peter Cushing, Stewart

Granger, Ferdinand Bonn, and Jeremy Brett.

In addition, there have been, according to Sherlockian Peter Blau of

Washington, D.C., and as of the summer of 1996, no fewer than 691 Sherlock

Holmes societies around the world, formed for the purpose of studying,

discussing and theorizing upon the sacred writings; 413 of these are still

active, the total count changing as new societies are formed and old ones

cease. The names of these societies have been as charming as the stories they

come from, the most famous being the Baker Street Irregulars in New York City,

founded by Christopher Morley in 1934 and still going strong.

Others have included, to name just a few listed in various lists:

| |

The Bootmakers of

Toronto, the Dancing Men of Providence, the Boulevard Assassins in Paris,

the Creeping Men of Cleveland, the Greek Interpreters of East Lansing, and

the Noble Bachelors (and Concubines) in Missouri;

|

| |

The Red-Headed

League, the Dead-Headed League, and the Black-Headed League;

|

| |

The Hollywood

Hounds, the Speckled Band in Boston, the 221Bees in Belgium, the Dog in

the Night-time in Seattle, the Mongooses of Henry Wood, the Lion's Mane of

Grand Rapids, the Giant Rats of Sumatra in Memphis, and the Silver Blazers

in Louisville;

|

| |

The Afghanistan

Perceivers of Oklahoma and the Messengers from Porlock in Tulsa;

|

| |

The Bruce

Partington Planners in Los Angeles, the Blanched Soldiers of the Pentagon,

and the Fifth Northumberland Fusiliers in Pittsburgh;

|

| |

The Arcadia

Mixture of Ann Arbor, the Trichonopoly Ashes, and the Agony Column of

Pasadena;

|

| |

The Agra

Treasurers, and the Ballarat Bushrangers;

|

| |

Boss McGinty's

Bird Watchers, the Lehigh Valley of Fear, and the Criterion Bar

Association;

|

| |

Dr. Watson's

Neglected Patients, and Watson's Erroneous Deductions;

|

| |

The Five Orange

Pips in Poughkeepsie, and the Pips of Orange County;

|

| |

the Reluctant

Scholars, the Retired Colonels, and the Napoleons of Crime;

|

| |

The Scion of the

four, the Sacred Six, and the Seventeen Steps;

|

| |

The Unslippered

Persians, and the Unanswered Correspondents;

|

| |

The Baritsu

Society of Japan, the Actas de Baker Street (now Circulo Holmes) in

Barcelona, and the Von Herder Airguns, Ltd in Germany.

|

Many have criticized these people for

fanatically clinging to an illusion of false reality and living in a dream

world. They appear, as did Walter de la Mare's Jim Jay, to have "got stuck

fast in yesterday." But Harry S. Truman, the only United States president

after FDR to be enrolled in the Baker Street Irregulars (as an honorary

member), may have hit upon a major reason for Holmes' popularity when he wrote

in 1945 to Edgar W. Smith, "Far from finding you, as you suggest, 'strange and

deluded creatures,' I commend your good sense in seeking escape from this

troubled world into the happier and calmer world of Baker Street."

There are Sherlock Holmes games, shirts, neckties, cards, towels, lamp

shades, and other memorabilia offered through catalogues. There are several

journals devoted to studying Holmes and anything associated with him, the best

of them being those published by the Baker Street Irregulars and the Sherlock

Holmes Society of London. There are comic books telling various tales of his

exploits; and he has been featured in comic strips, advertisements, posters

and billboards. Pubs, taverns and restaurants from London to Los Angeles bear

his name. There are Sherlock Holmes games, shirts, neckties, cards, towels, lamp

shades, and other memorabilia offered through catalogues. There are several

journals devoted to studying Holmes and anything associated with him, the best

of them being those published by the Baker Street Irregulars and the Sherlock

Holmes Society of London. There are comic books telling various tales of his

exploits; and he has been featured in comic strips, advertisements, posters

and billboards. Pubs, taverns and restaurants from London to Los Angeles bear

his name.

Many famous Sherlockiana collectors and writers have amassed huge

libraries containing thousands of books, periodicals, and collectibles, and

many of them are donating their collections to the University of Minnesota,

which is planning a Sherlock Holmes Center to house them all. The Internet

hosts a massive and still-growing list of Holmes entries, including an

electronic mailing list called The Hounds of the Internet, a news group

reached by dialing alt.fan.holmes, and a dozen or more Sherlockian home pages

on the World Wide Web. And the British Library in London, the Colorado State

University Library, the San Francisco Public Library, the Metropolitan Toronto

Library, and the U.S. Library of Congress also have large numbers of Holmes

books. Card catalogues are usually accessible on-line. Among private

collectors, the late John Bennett Shaw of Santa Fe, New Mexico, owned the

largest private collection in the world, which he bequeathed to the University

of Minnesota.

But it gets wilder than that. As far back as 1931 Arthur Wontner, the

premier screen Holmes until Rathbone, wrote, "there are parts of the world

today where Conan Doyle's fictitious rival to Scotland Yard is not only

believed to be an authentic personality, but is actually held to be alive."

Vincent Starrett described Holmes two years later as "a figure of incredible

popularity, who exists in history more surely than the warriors and statesmen

in whose time he lived and had his being. An illusion so real, as Father

[later Monsignor] Ronald Knox has happily suggested, that one might some day

look about for him in Heaven, forgetting that he was only a character in a

book."

The detective and his Boswell are believed to be there yet, two men

who never lived at an address that never existed. To this day, several hundred

letters a month to Holmes are received and answered by the staff of the Abbey

National Bank on Baker Street, of which 221 is one of its office numbers.

These letters include Christmas cards (one comes every year from Watson),

birthday cards, wedding invitations, speaking requests, and ~ of course ~

mysteries to investigate. Holmes has been asked to resolve Watergate, the

energy crisis, the Cold War and the nuclear arms race. Some letters convey

news of the whereabouts of Professor Moriarty, who appears to be seen almost

as often as Elvis. Some even notify Holmes that he may be eligible to win

millions of dollars in the next lottery drawing.

The $64,000 Question

Finally, the question which remains is: Why such keen interest, such

fanatical devotion to this irascible character from people in all walks of

life, on every continent, in every era?

For one thing, there is in the Holmes-Watson portrait a sense of

personal realism, a basic human quality, lacking in other sagas. Neither Dupin

nor Lecoq were anywhere near so human, and James Bond, Matt Helm (played by

Dean Martin in a series of 1960s films), and other television and film secret

agents are almost one-dimensional, like cardboard cutouts. Holmes and Watson

are intensely life-like, with all-too-human limitations and weaknesses.

Holmes' asocial personality may certainly be abnormal, but it is perfectly

realistic. And Watson ~ solid, honest, conventional ~ is in tune with his

emotions and their expression: he not only reacts variably to Holmes's moods

and outbursts, but on more than one occasion he leaves the singular romance of

Baker Street for the greater romance of marriage.

Holmes was distinctive, even eccentric, asocial, manic-depressive, and

friendless except for Watson. In the beginning Watson had listed various

points about Holmes: He lacked any knowledge of literature, philosophy,

astronomy, and politics. His knowledge of botany was variable, with a sound

knowledge of poisons. His knowledge of geology was practical but limited; he

knew at a glance different soils and their locations. His knowledge of

chemistry was profound, his knowledge of anatomy was accurate but

unsystematic, and his knowledge of sensational literature was immense,

knowing, as he did, "every detail of every horror perpetrated in the century."

Holmes played the violin well. He was an expert single-stick player, boxer,

and swordsman. And he had "a good practical knowledge of British law."

Holmes was given to indoor target practice and self-inflicted

injections of cocaine at a time when such casual recreational use was far more

acceptable, and the drugs far more easily obtained over any pharmaceutical

counter, than today. He was a man whose mind he likened to a racing engine,

tearing itself to pieces when not connected with the work for which it was

built. His was a genius constantly in need of feeding.

Jeremy Brett observed, "He is complex. He loves music ~ he plays the

violin very well ~ he enjoys a joke, he is vain, maybe a little conceited. He

likes to be praised. He can be bitchy when he assesses other great detectives.

On a difficult case he may build up considerable tension within himself, which

explodes in a genial bit of theatricality when the problem is solved."

Basil Rathbone spent years playing the role of Holmes and wrote that

"toward the end of my life with him I came to the conclusion...that there was

nothing lovable about Holmes. He himself seemed capable of transcending the

weakness of mere mortals such as myself...understanding us perhaps, accepting

us and even pitying us, but only and purely objectively. It would be

impossible for such a man to know loneliness or love or sorrow because he was

completely sufficient unto himself. His perpetual seeming assumption of

infallibility; his interminable success; (could he not fail just once and

prove himself a human being like the rest of us!) his ego that seemed at times

to verge on the superman complex, while his 'Elementary, my dear Watson,' with

its seeming condescension for the pupil by the master must have been a very

trying experience at times for even so devoted a friend as was Dr. Watson.

"One was jealous of Holmes of course... Jealous of his mastery in all

things, both material and mystical...he was a sort of god in his way, seated

on some Anglo-Saxon Olympus of his own design and making! Yes, there was no

question about it, he had given me an acute inferiority complex!"

Holmes obviously craved center-stage. When Watson had published an

account of their first case together, A Study In Scarlet, Holmes was

disappointed. "Detection is, or ought to be, an exact science," he said, "and

should be treated in the same cold and unemotional manner. You have attempted

to tinge it with romanticism, which produces the same effect as if you worked

a love-story or an elopement into the fifth proposition of Euclid..." And

Watson was miffed at Holmes' blatant self-preoccupation.

He was certainly a housekeeper's nightmare, and those less inclined to

the conventional will find in him a kinsman. As Watson wrote in The

Musgrave Ritual: "When I find a man who keeps his cigars in the

coal-scuttle, his tobacco in the toe-end of a Persian slipper, and his

unanswered correspondence transfixed by a jackknife into the very centre of

his wooden mantelpiece, then I begin to give myself virtuous airs."

He was a sophisticated gastronome who appreciated good food and fine

wine. He was also quite fashion-conscious, going about properly and

meticulously dressed at all times. One of his trademarks, the deerstalker cap,

was actually a hunting cap, as its name implies, and was strictly country

apparel. Thus, he wore it (or, rather, is pictured wearing it by Paget,

for it is not mentioned in the canon) only on cases which took him to the

country. In town, he wore a top hat and tails, a bowler, or some other

appropriate headgear.

The deerstalker cap, of course, as well as the Inverness cape and the

curved pipe, were all made famous by William Gillette when he donned them for

his performances as Holmes on stage. The cap and cape were subsequently

introduced into the legend by Sidney Paget.

Holmes had an exceptional ear for music, owned and played a

Stradivarius, and was, in Watson's words, "not only a very capable performer,

but a composer of no ordinary merit." He often attended concerts given by

famous violinists of the era, and he favored German music over others. The

Stradivarius, of course, was very often used in meditative moods, during which

times he simply scraped the bow across the strings, the instrument draped

across his knees, producing sounds that reflected his thoughts but wore

savagely on Watson's nerves. When he played good music, even difficult music,

"with vigor and virtuosity" as one writer called it, he used no sheet music,

playing strictly by ear.

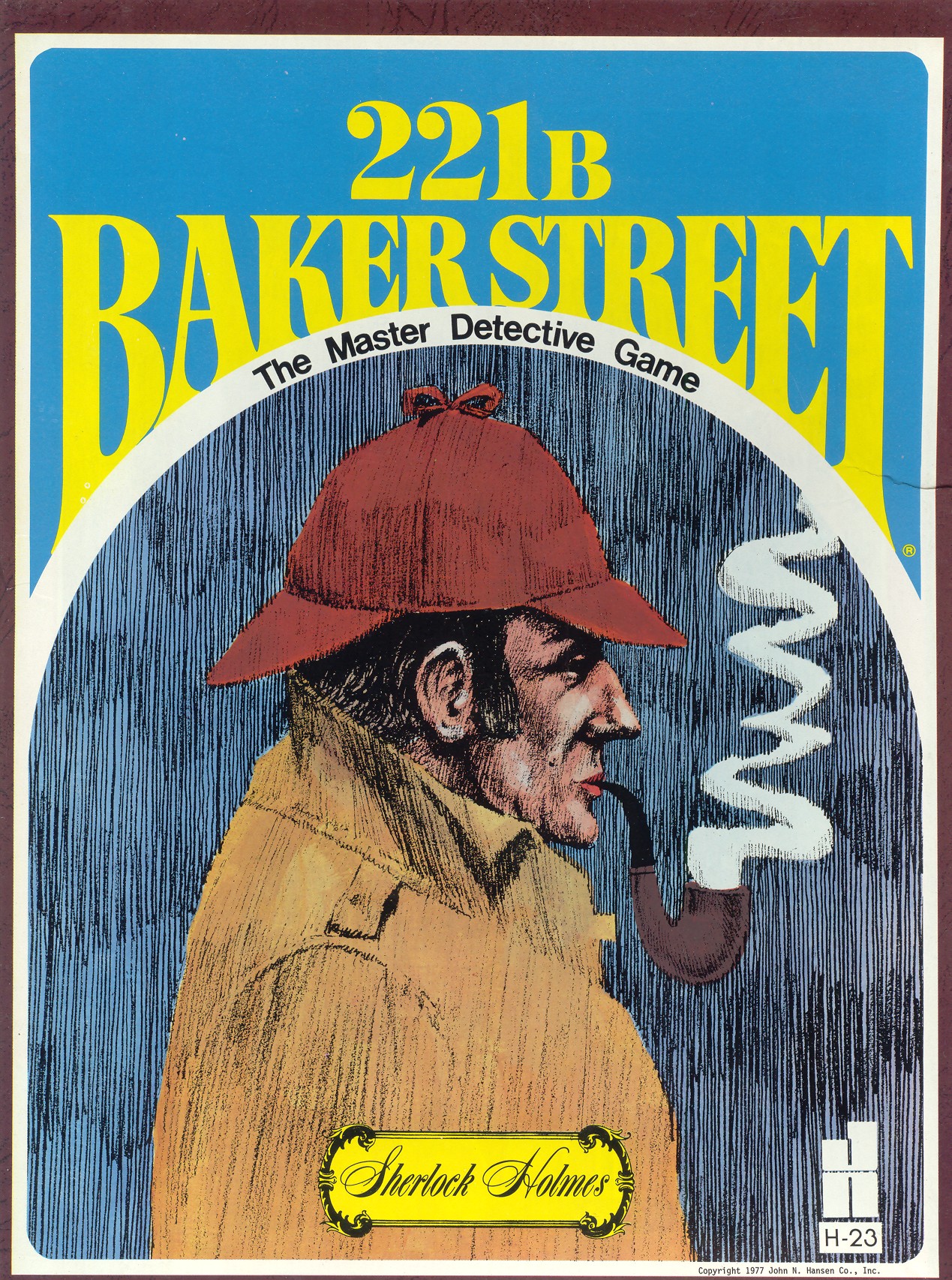

While Holmes smoked cigarettes and a very rare cigar, he most often

smoked a pipe. His favorite was a clay pipe, which he smoked at home and

preferred as the companion of his ruminative moods. He smoked the cherrywood

when in a disputatious mood, and always had his briars. Interestingly, Holmes

was never pictured smoking the calabash pipe, even though this pipe was known

in England by the end of the 19th century. Whether he smoked one or not, they

also would have been too cumbersome and fragile to carry about, since the

gourd which makes up so much of its shape is rather easily crushed. It has

been claimed repeatedly that Gillette (smoking at right) had discovered that

it is easier to speak with a bent briar clenched between his teeth than with a

straight pipe, and that he began using it on stage for that reason. It, and

the calabash, have been identified with Holmes ever since. While Holmes smoked cigarettes and a very rare cigar, he most often

smoked a pipe. His favorite was a clay pipe, which he smoked at home and

preferred as the companion of his ruminative moods. He smoked the cherrywood

when in a disputatious mood, and always had his briars. Interestingly, Holmes

was never pictured smoking the calabash pipe, even though this pipe was known

in England by the end of the 19th century. Whether he smoked one or not, they

also would have been too cumbersome and fragile to carry about, since the

gourd which makes up so much of its shape is rather easily crushed. It has

been claimed repeatedly that Gillette (smoking at right) had discovered that

it is easier to speak with a bent briar clenched between his teeth than with a

straight pipe, and that he began using it on stage for that reason. It, and

the calabash, have been identified with Holmes ever since.

However, Al Shaw's excellent treatment of the history of curved pipes

in the 19th century (TPSE, Winter-Spring 1994) makes it clear that

curved briars were very much available to Holmes and that he did not

necessarily smoke only straight pipes, as Paget made it seem. Whether he did

or not is mere speculation, but it is as difficult to speak clearly with a

bent pipe clamped between one's teeth as it is with a straight pipe, so one

must question the veracity of this claim.

Whatever his reason, Gillette’s choice of pipes left a lasting

impression. Danish actor Alwin Neuss smoked a bent meerschaum in Den

Stjaalne Million-Obligation in 1908, and Norwood, Brook, Wontner and

Rathbone smoked bent briars in their films. The true calabash pipe, a more

colorful instrument made from a gourd and sporting a meerschaum bowl, was

smoked by Rathbone, and it appeared briefly (according to John Hall’s 140

Different Varieties, A review of tobacco in the Canon, published by the

Northern Musgraves Sherlock Holmes Society in England) in 1965's A Study in

Terror, and again in 1970's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes

starring Robert Stephens. It has appeared in nearly all Holmes films ever

since with the notable exception of the Granada series, in which Jeremy Brett

returned to the clay, the straight briar and the church warden.

While Holmes remains the epitome of the pipe-smoker, as such he was

both uncouth and careless. Alan Smith analyzed his smoking habits in The

Compleat Smoker (Vol. 1, No. 3, Spring 1991): Holmes kept his cigars in a

coal scuttle (the conventional Watson kept his own cigars in a humidor) and

his pipe tobacco in the toe-end of a Persian slipper. At the end of each smoke

he would knock the plugs and dottle out onto the mantlepiece to dry overnight

and, the next day, would gather them up, pack them into a pipe, and light up.

He abused his pipes by lighting them with burning coals from the fireplace and

by chain-smoking the same pipe for hours; and Watson's description of his

favored clay pipe ~ "old and oily clay" and "his black clay pipe" ~ shows he

rarely, if ever, cleaned it, preferring to smoke it into what Smith referred

to as "foul, black oblivion."

Holmes's tobacco was no exotic mixture. He smoked black "shag," an

ignoble tobacco blended from the strongest and worst kind of leaf, and smoked

only by the poorer classes of society. By keeping it in his Persian slipper,

or in pouches over the mantle, he kept it perpetually dry, which caused it to

smoke faster and hotter than normal. And since he rarely, if ever, cleaned his

pipes, the resulting smoke was sour and offensive to those around him. "You

have not, I hope, learned to despise my pipe and my lamentable tobacco," he

once said to Watson. It is worth noting, however, that smoking shag not only

helped him think (it certainly would have kept him awake), it enabled him to

blend in with the lower classes when he was in disguise and in need of

information. Watson smoked "Ships," which would have been Shippers Tobak

Special from Holland. He also smoked an Arcadia mixture which Holmes sampled

at least once that we know of.

Finally, pipes were important to Holmes in sizing up a man: "Pipes are

occasionally of extraordinary interest," he said in "The Yellow Face."

"Nothing has more individuality save, perhaps, watches and bootlaces."

Holmes, the Man

Much has been made of Holmes's attitude toward women. That he

distrusted them is certain: "Women are never to be entirely trusted ~ not the

best of them." Yet he often gave them their due: "I have seen too much not to

know that the impression of a woman may be more valuable than the conclusion

of an analytical reasoner." He denied hating women, yet was uncomfortable with

displays of feminine affection, and once told Watson, "Love is an emotional

thing, and whatever is emotional is opposed to that true, cold reason which I

place above all things." Is there more outright withdrawal here, however, than

plain reason?

He claimed to be unromantic, this man who was swept into rhapsody by

the music of Mendelssohn and Wagner, and who, in the midst of a sinister

investigation, waxed poetic over a rose. With great gentleness but a firm

will, he reminded the horribly scarred veiled lodger that her life was not her

own.

Misogynistic? Not quite; but emotionally crippled, to be sure.

Misogyny is a psychopathic emotional condition in which the misogynist has an

irrational hatred and fear of women (or, in the case of women sufferers,

called misandrists, a pathological hatred of men). To a great degree (except

for the pathological hatred), this fits Holmes. This condition is additionally

characterized by explosive tirades, manipulation, a lack of integrity, and

emotional and sometimes physical abuse, of which Holmes, however the

dramatist, was not guilty. It is also characterized by a genuine dearth of

empathy and conscience, qualities Holmes did not lack. Misogynists are abusive

for the sole purpose of control: if a wife (or husband) can be controlled, the

abuser cannot be hurt. Holmes certainly tried to maintain control, and can it

always be said that his purposes were more altruistic than the mere avoidance

of being hurt?

Another label that could be applied to Holmes is that of the

misanthrope, one who hates or mistrusts all people, male and female.

Holmes certainly had a wide circle of acquaintences and associates but

discouraged friendships, having only one real friend, Watson, although

Reginald Musgrave had been an earlier chum. His correspondence was limited

and, being manic-depressive, he was often reclusive and sullen. Yet, when the

mania took over from the depression, he was lively, friendly and active. Yet

he was still the loner except for his Boswell.

Psychological studies of Holmes and Doyle could occupy volumes. He may

have been to some degree misanthropic, and one can distrust women without

truly hating them; in fact, perhaps the main reason why Holmes was not totally

misogynistic was because Doyle himself was not. Sir Arthur idolized women;

and, as alike and yet different though they were, he could hardly have his

detective truly hate the fair sex.

With Watson, of course, there was a comfortable distance: two

Victorian gentlemen, sharing the truest of friendships ~ the depth and nature

of which would not be understood in today's fast-paced and transient society ~

as well as lodgings and adventures, but never their innermost secrets. After

all, how long had they lived together before either knew that his

fellow-lodger had a brother?

Thus, we see that he could be very amiable and warm, compassionate and

just, and morally upright. As Carr astutely pointed out, "We can scarcely dip

into the stories anywhere without finding Holmes telling us how unemotional he

is, and in the next moment behaving more chivalrously ~ especially towards

women ~ than Watson himself."

He let mercy overrule legal considerations: "I suppose that I am

commuting a felony, but it is just possible that I am saving a soul. This

fellow will not go wrong again." And, "Once or twice in my career I feel that

I have done more real harm by my discovery of the criminal than ever he had

done by his crime. I have learned caution now, and I had rather play tricks

with the law of England than with my own conscience."

Small wonder that Watson called him "the best and the wisest man whom

I have ever known." And A. E. Murch described him as being "the most

convincing, the most brilliant, the most congenial and well-loved of all

detectives of fiction."

The Legend Is Us

This is the man we cannot resist. Higham wrote that "after only a few

years, the Sherlock Holmes stories had assumed the status of fairy tales ~

magical, improbable, buoyed up by an imagination as inexhaustible as that of

Hans Christian Andersen or the brothers Grimm... The people of an increasingly

scientific age yearned for fantasy, for magic, and for wild adventure."

Christopher Morley added: "The whole Sherlock Holmes saga is a

triumphant illustration of art's supremacy over life... It is not that we take

our blessed Sherlock too seriously... Holmes is pure anesthesia." Never was

this more evident than in the case of Jeremy Brett. When Brett’s wife,

American television producer Joan Wilson, died from cancer in 1985, Brett

dealt with his grief by absorbing himself in his new role as Holmes. I turned

to Holmes, immersed myself, Brett later admitted. It seemed to keep me going

without her.

But there is more to Sherlock Holmes than mere anesthesia. The

atmosphere itself beckons. One of the finest Sherlockians of all time was

Edgar W. Smith, vice president of the General Motors Corporation. Smith wrote,

"We love the times in which he lived, of course, the half-remembered,

half-forgotten times of smug Victorian illusion, of gas-lit comfort and

contentment, of perfect dignity and grace...

"And we love the place in which the Master moved and had his being:

the England of those times, fat with the fruits of her achievements, but

strong and daring still with the spirit of imperial adventure... It was a

stout and pleasant land full of the flavor of the age; and it is small wonder

that we who claim it in our thoughts should look to Baker Street as its

epitome..."

We yearn for what now seems to have been a simpler world beneath the

civilizing rays of Victoria's scepter, before the Titanic sank in 1912 and,

with it, our unbridled faith in our own technology; and before the Great War

swept away that world forever, leaving in its wake political, economic and

military chaos that has only increased in the decades since. It is no wonder

that we wish all the more for the quiet Victorian serenity of Baker Street.

But there is something else in the adventure that fascinates us as

this tall, lean figure, candle in hand, shakes Watson awake in the early hours

of the morning. "Come, Watson, come! The game is afoot!" Our hearts beat

faster as we join Holmes afoot, and perhaps here is where the bond really

begins. As Stefan Kanfer wrote in Time, "Doyle's genius was in creating

a person not so different from ourselves ~ and then splitting him in half. One

part is a fallible, well-meaning soul who works at a job. The other is the

person we would aspire to be: morally correct, financially independent and

underweight. One feels; the other knows. One is real; the other ideal. Many

labels adhere to this classic combination: ego and superego, desire and

conscience, Watson and Holmes."

And Edgar Smith continued "Not only there and then, but here and now,

he stands before us as a symbol...of all that we are not, but ever would be...

We see him as the fine expression of our urge to trample evil and to set

aright the wrongs with which the world is plagued. He is Galahad and Socrates,

bringing high adventure to our dull existences and calm, judicial logic to our

biased minds. He is the success of all our failures; the bold escape from our

imprisonment."

Holmes is, Smith argued, "the personification of something in us that

we have lost, or never had. For it is not Sherlock Holmes who sits in Baker

Street, comfortable, competent and self-assured; it is ourselves who are

there, full of a tremendous capacity for wisdom, complacent in the presence of

our humble Watson, conscious of a warm well-being and a timeless, imperishable

content. The easy chair in the room is drawn up to the hearthstone of our very

hearts ~ it is our tobacco in the Persian slipper, and our

violin lying so carelessly across the knees ~ it is we who hear the

pounding on the stairs and the knock upon the door. The swirling fog without

and the acrid smoke within bite deep indeed, for we taste them even now. And

the time and place and all the great events are near and dear to us not

because our memories call them forth in pure nostalgia, but because they are a

part of us today.

"That is the Sherlock Holmes we love ~ the Holmes implicit and eternal

in ourselves."

* * * * * * *

Holmes retired in 1903 to keep bees on the Sussex Downs and to write

his two masterpieces, The Practical Handbook of Bee Culture with some

Observations upon the Segregation of the Queen, which Holmes referred to

as the fruit of pensive nights and laborious days, and The Whole Art of

Detection, on which he expected his lasting fame to deservedly rest,

rather than on those romanticized tales by Watson. Down through the years new

cases have appeared, some mentioned in the canon but never published, others

heretofore unheard of, each one "discovered" either in some old attic trunk or

in that battered old tin dispatch box at Cox & Company, with "John H. Watson,

M.D." printed on the lid.

For myself, I never cease searching for a new Holmes mystery to dive

into. Devouring each as I find it, I am always downcast once the adventure

ends. Like so many others, and probably for all the reasons cited above, I am

loathe to leave that little romantic chamber of the heart, that nostalgic

country of the mind, where the game is afoot and the deductions are elementary

and the evil Moriarty is up to no good.

And where it is always, forever, 1895.

© 2006 Henry Zecher

[ Home ] [ Book Signing ] [ Slide Show Presentation ] [ Contact Mr. Zecher ] [ Martin Luther ] [ Bing Crosby ] [ Draculean Theory ] [ Gillette Short Bio ] [ Good Sheperd ] [ Grandfather Clock ] [ People Will Come! ] [ Plagues ] [ Purchase Book ] [ Tom Dunn ] [ Zecher Short Bio ] [ Sherlock Holmes ] [ Papyrus Ipuwer ] [ Hugs ] [ George Burns ] [ Gay's Tub Couple Cartoon ] [ C. S. Lewis ] [ Selected Bibliography ]

|

There are Sherlock Holmes games, shirts, neckties, cards, towels, lamp

shades, and other memorabilia offered through catalogues. There are several

journals devoted to studying Holmes and anything associated with him, the best

of them being those published by the Baker Street Irregulars and the Sherlock

Holmes Society of London. There are comic books telling various tales of his

exploits; and he has been featured in comic strips, advertisements, posters

and billboards. Pubs, taverns and restaurants from London to Los Angeles bear

his name.

There are Sherlock Holmes games, shirts, neckties, cards, towels, lamp

shades, and other memorabilia offered through catalogues. There are several

journals devoted to studying Holmes and anything associated with him, the best

of them being those published by the Baker Street Irregulars and the Sherlock

Holmes Society of London. There are comic books telling various tales of his

exploits; and he has been featured in comic strips, advertisements, posters

and billboards. Pubs, taverns and restaurants from London to Los Angeles bear

his name.  While Holmes smoked cigarettes and a very rare cigar, he most often

smoked a pipe. His favorite was a clay pipe, which he smoked at home and

preferred as the companion of his ruminative moods. He smoked the cherrywood

when in a disputatious mood, and always had his briars. Interestingly, Holmes

was never pictured smoking the calabash pipe, even though this pipe was known

in England by the end of the 19th century. Whether he smoked one or not, they

also would have been too cumbersome and fragile to carry about, since the

gourd which makes up so much of its shape is rather easily crushed. It has

been claimed repeatedly that Gillette (smoking at right) had discovered that

it is easier to speak with a bent briar clenched between his teeth than with a

straight pipe, and that he began using it on stage for that reason. It, and

the calabash, have been identified with Holmes ever since.

While Holmes smoked cigarettes and a very rare cigar, he most often

smoked a pipe. His favorite was a clay pipe, which he smoked at home and

preferred as the companion of his ruminative moods. He smoked the cherrywood

when in a disputatious mood, and always had his briars. Interestingly, Holmes

was never pictured smoking the calabash pipe, even though this pipe was known

in England by the end of the 19th century. Whether he smoked one or not, they

also would have been too cumbersome and fragile to carry about, since the

gourd which makes up so much of its shape is rather easily crushed. It has

been claimed repeatedly that Gillette (smoking at right) had discovered that

it is easier to speak with a bent briar clenched between his teeth than with a

straight pipe, and that he began using it on stage for that reason. It, and

the calabash, have been identified with Holmes ever since.![]()