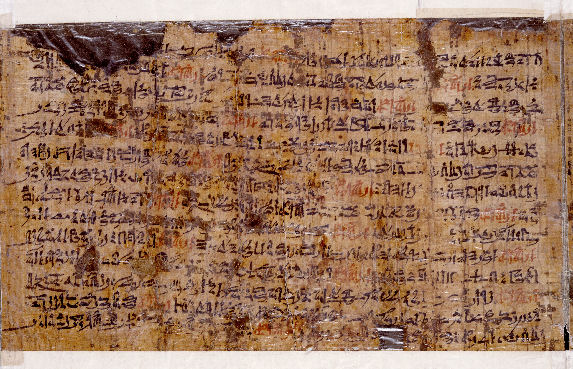

The Papyrus Ipuwer,

Egyptian Version of the Plagues ~

A New Perspective

[Published in The Velikovskian, January 1997; this was the first scholarly work in nearly half a century to challenge Immanuel Velikovsky’s view of the Papyrus Ipuwer as an Egyptian version of the plagues described in the Book of Exodus, and yet show that Velikovsky’s connection of the two was correct]

By Henry Zecher

In the spring of 1940, Immanuel Velikovsky (left) pondered what kind

of natural catastrophe had turned the plain of Sodom and Gomorrah into the

lake which Joshua and the Israelites came upon after the Exodus. He pondered

the plagues described in the Book of Exodus, whether or not they were real and

whether or not there was an Egyptian version of them.

In search of just such a document, he soon discovered in a reference

book the mention of an Egyptian papyrus by a sage named Ipuwer declaring that

the Nile River was blood. Locating and studying the English translation of the

papyrus by Alan Gardiner, he was struck by the fact that the papyrus seemed to

be a description of a great natural disaster. To Velikovsky, however, it

appeared to be more than that. He believed he had found an Egyptian version of

the plagues described by Moses in the Old Testament Book of Exodus.

"All the waters that were in the river were turned to blood," Moses had written. "The river is blood," Ipuwer concurred.

Moses wrote that "the hail smote every herb of the field, and brake every tree of the field." Ipuwer lamented, "Trees are destroyed" and "No fruit nor herbs are found..."

Finally, Moses wrote that "there was a thick darkness in all the land of Egypt." As Ipuwer succinctly put it, "The land is not light."

Verses common to both sources told of Egyptians searching frantically

for water, the death (or loss) of fish and grain, massive destruction of trees

and crops, plague upon the cattle, a great cry (or groaning) throughout the

land, a consuming fire, darkness, and the escape of slaves. Moses did not

specifically say that the pharaoh had perished in the Red Sea, but Ipuwer

lamented the king's disappearance at the hands of poor men under circumstances

that had never happened before.

Published in full for the first time in Gardiner's The Admonitions

of an Egyptian Sage from a Hieratic Papyrus in Leiden in 1909, the now

famous Papyrus Ipuwer launched Velikovsky on a mission that would consume the

rest of his life. In very short order he became, as he put it, "the prisoner

of an idea." That idea ~ all-encompassing and interdisciplinary ~ was the

recent cataclysmic history of the earth and the solar system, and a

reconstruction of the history of ancient Egypt. "I realized," Velikovsky

explained, "that the Exodus had occurred in the midst of a natural upheaval

and that this catastrophe might prove to be the connecting link between the

Israelite and Egyptian histories, if ancient Egyptian texts were found to

contain references to a similar event. I found such references and before long

had worked out a plan of reconstruction of ancient history from the Exodus to

the conquest of the east by Alexander the Great."1

The Papyrus Ipuwer (above) describes the

final act in the downfall of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, an event which began

the Second Intermediate Period in Egyptian history and which coincided with

the story of the Exodus recorded by Mosesin the Scriptures. Followers of

Velikovsky's work are well aware of the list of

parallel verses first published in Pensee. It's an impressive list.

"Professor J. Garstang, excavator of Jericho, read an early draft of the first

chapter (of Ages in Chaos)," Velikovsky wrote. "It was his opinion that the

Egyptian record of the plagues, as set

forth in this book, and the biblical passages dealing with the plagues are so

similar that they must have had a common origin."2

The operative phrase, however, is "as set forth in this book."

Velikovsky took liberties in lifting many of the Egyptian's words out of their

original context and then holding them up alongside the Scriptures as

contemporaneous parallels. A reading of the text of the Admonitions, in

fact, leads one to suspect that Ipuwer was not really describing the plagues

at all, but in part their aftermath in the context of the invasion that

followed and the devastation wrought by that invasion. Velikovsky was often

accused of psychoanalytically drawing more interpretation out of a single

source than it really had to give, and of either misinterpreting or

selectively interpreting sources that would support his thesis. In this case

it would appear that he did just that.

The synchronism, however, is still valid, and Velikovsky was quite

right to connect the two accounts. But, rather than simultaneously describing

the same plagues, it appears that Moses recorded Act I of the drama: the

devastation of Egypt and the escape of the Israelites at the hand of the Lord;

and that Ipuwer described Act II: the conquest of Egypt by the Hyksos on the

heels of the Exodus. Velikovsky identified the Hyksos as the Biblical

Amalekites3 whom the Israelites battled in the desert at Rephidim after

crossing the Red Sea.4 That provides a further link between the two accounts.

Yet, by focusing on Velikovsky's belief that it was an Egyptian

version of the plagues, we have missed entirely the true meaning of the

Admonitions and its importance to the history of the world's literature.

And the Papyrus, though important to the Exodus story, may not be quite what

Velikovsky thought it was.

The Papyrus Ipuwer was one of the most important documents in the

history of the world's early literature. It was, so far as we know, the first

true example of free speech in the ancient totalitarian world and of Messianic

prophecy at a time of national crisis. Many authors have referred to it in

their writings and listed it in their handbooks and encyclopedias, but few

have truly understood what it really was. Of those who did, the

American James Henry Breasted and the German Adolf Erman had the most to

offer. And it was Velikovsky who first viewed it in the light of its place in

Hebrew history by its relation to the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt.

The papyrus was first discovered in Memphis (or Sakkara), having

belonged to one Anastasi, who sold it along with the rest of his antiquities

to the Leiden Museum in 1828. The papyrus measures 378 centimeters in length

and is 18 centimeters high. Both sides were fully inscribed, the recto

consisting of 17 pages ~ some complete, some not ~ of writing in the type of

hieratic signs used by scribes, and the verso containing hymns to a solar

deity written during either the 19th or the 20th Dynasty. The papyrus is

folded into a 17-page book, but the beginning is missing, and there are

several gaps within. The writing, the spelling, and the language of the recto

text are all characteristic of the late Middle Kingdom.

"Each page (of the recto) had fourteen lines of writing, so far as we

were able to judge," Gardiner wrote, "with the exception of pages 10 and 11,

which had only thirteen lines apiece. Of the first page only the last third of

eleven lines remains. Pages two to seven are comparatively free from lacunae

(gaps), but in many places the text has been badly rubbed. A large lacuna

occurs to the left of page eight, and from here onwards the middle part of

each page is entirely or for the greater part destroyed. The seventeenth page

was probably the last; at the top are the beginnings of two lines in the small

writing typical of the recto; near the bottom may be seen traces of some lines

in a larger hand apparently identical with that of the verso."5

A facsimile copy of the papyrus itself was first published by Conrad

Leemans in 1846; and, in an introduction to Leemans' book, Francois Chabas

commented that the first eight pages contained axioms and proverbs while the

following fragmentary pages were philosophic in nature. Franz Lauth translated

the first nine pages in 1872, interpreting the text as a collection of

proverbs or sayings used by the Egyptians for didactic purposes.

German Egyptologist Heinrich Brugsch was quoted by Erman, and also by

Hans Lange in his 1903 paper titled Prophezeiungen eines ägyptischen Weisen,

as considering the papyrus to be a collection of riddles; but in 1904 Lange,

having studied it intensely and translated many of its passages, informed the

Berlin Academy of Sciences that the text contained "the prophetic utterances

of an Egyptian seer."

It may seem preposterous that anyone could read this papyrus and think

it contains riddles, prophecies, axioms or proverbs, but it was in such a bad

state of preservation, and parts of it were so obscure and difficult to

understand, that few in those early days of Egyptology could even begin to

grasp its true content and meaning. Gardiner even made special mention of "the

extreme corruption of our papyrus... It is not unlikely that the scribe of the

Leiden manuscript was himself responsible for a considerable number of the

mistakes. A particularly large class of corruptions is due to the omission of

words."6

The reading of hieroglyphics was still a young and slowly developing

science in the last century, so the first real translation of the

Admonitions was not achieved until 1872, and then it was just the first

nine pages translated by Lauth. Brugsch quoted many sentences in the

Supplement to his Hieroglyphic Dictionary, but he never printed his view of

the text as a whole and, in fact, did not appear to perceive it as being a

continuing narrative at all. France's Gaston Maspero gave several lectures on

it at the Ecole des Hautes Etudes, but up to this time the Admonitions

was thought to be composed of separate and independent sayings.

It was Lange, Chief Librarian of the Royal Academy at Copenhagan, who

in 1903 demonstrated that the text was in fact a continuous whole. He

furthermore declared that it was of poetical and semi-philosophical nature,

prophetic (actually Messianic) in meaning, with linguistic ties to such Middle

Kingdom literature as the Instructions of Amenemhet I and A Dispute

Over Suicide. It was apparently spoken to the king who was responsible for

a coming era of disaster being predicted in the papyrus. "The characteristic

feature of this group of Middle Kingdom texts," Gardiner explained, "is that,

while the setting is that of a tale, the claim that they made to the

admiration of their readers lay wholly in the eloquence and wisdom of the

discourses contained in them."7

In 1905, Lange was contacted by Gardiner, one of the 20th century's

foremost Egyptologists whose work over more than half a century greatly

advanced our understanding of hieroglyphics. The two men read through the

entire papyrus in Copenhagen, and Gardiner was able to establish an accurate

text; but, although they had intended to collaborate on a book, official

duties and ill health forced Lange to withdraw from the project. Alone now

except for Lange's council, Gardiner obtained indispensable assistance from

German Professor Kurt Sethe, who studied Gardiner's entire manuscript and

furnished suggestions and criticisms. They accomplished much in reaching an

understanding of its meaning, even though parts of it refused to yield their

secrets, as many still do today.

While Gardiner and Sethe had trouble understanding what it meant,

since the beginning is missing and the last eight pages have been reduced by

lacunae to half their original bulk, it is easy to see that, as Gardiner

explained it, "the Egyptian author had divided and subdivided his book, or

rather the greater part of what is left of it, by means of a small number of

stereotyped introductory formulae, which consist of a few words or a short

clause usually written in red and repeated at short intervals. New reflexions

or descriptive sentences are appended to these formulae, which thus form as it

were the skeleton or the framework of the whole." The mode of composition is

monotonous, like parts of the Dispute Over Suicide and other early

works. "The first part contains the 'Messianic' passage to which Dr. Lange

called special attention. This leads into a passionate denunciation of someone

who is directly addressed and who can only be the king; after which the text

reverts to the description of bloodshed and anarchy."8

It appeared to Gardiner that the king's speech was contained in the

damaged 14th or 15th page, but the speaker who addressed the king throughout

was Ipuwer. Apparently, since Ipuwer reverted on occasion to the second person

plural, courtiers of the king were also present.

Lost to us are any clues to the position or personality of the author

in the damaged narrative which "must have introduced and preceded the lengthy

harangue of Ipuwer, and about the circumstances that led to his appearance at

the court of the Pharaoh." The insightful Erman, however, hazarded a guess:

"In view of the frequent references to storehouses and treasuries, it is

natural to suppose that the sage was one of the treasury officials. Also...it

may be inferred that he came from the Delta to report on the lack of treasure;

possibly he had to do this himself, because his messengers refused to go. The

catastrophe, however, is not confined only to the Delta, but extends, as is

expressly stated...to Upper (southern) Egypt."9

But whoever or whatever he was, one thing is clear: "Ipuwer was no

dispassionate onlooker at the evils which he records. He identifies himself

with his hearers in the question what shall we do concerning it? evoked

by the spectacle of the decay of commercial enterprise; and the occupation of

the Delta by foreigners, and the murderous hatred of near relatives for one

another, wring from him similar ejaculations."

While Lange believed the text to be a predictive prophecy foretelling

the future, Gardiner determined that it was a description of current and past

events. Prophets may present their forewarning in the present or past tense,

Gardiner suggested, but never in such detail as Ipuwer employed. "The entire

context from 1,1 to 10,6 constitutes a single picture of a particular moment

in Egyptian history," he concluded, "as it was seen by the pessimistic eyes of

Ipuwer."10

Eduard Meyer not only thought it prophetic, however, he saw the

papyrus as having a bearing on ancient Hebrew Messianic prophecies. This

Messianic character of the papyrus was upheld by T. E. Peet two decades later:

"In the first place it is the purely physical product of the distressful days

of the (First) Intermediate Period, whether we believe that some or all of it

was actually written during that time or immediately after. And in the second

place it reflects...the awakening of man to the moral unworthiness of society

and the possibility of better things. In Petrograd 1116B a saviour is actually

predicted, and again, in the Admonitions of Ipuwer, although there is no

prediction, the poet cannot refrain from drawing a picture of the ideal ruler

of a state under the form of the sun-god Re. This type of writing, whether

definitely predictive or not, is closely akin to the prophetic writings of the

Hebrews, and every discussion of the latter must reckon with the possibility

of Egyptian models."11

Interpretation of the Messianic nature of the Admonitions is no

flight of fancy; but, to appreciate what a landmark achievement Ipuwer's was,

we need to look back to the literature which preceded him.

Among other reasons for the late Middle Kingdom date assigned to the

Admonitions is the fact that Egyptian literature simply had not

developed to that level by the end of the Old Kingdom. David Roberts recently

revealed in National Geographic that, from its early dynastic

beginnings, when early Egyptians dug canals to irrigate their fields and

transport building materials such as timber and huge blocks of stone, "local

agriculture became the force that knit together the kingdom's economy. The

need to keep records of the harvest may have led to the invention of a written

language."

That did not mean, however, that a newly invented language would

produce a mature literature. "We know of no literature until around 2400 B.C.,

near the end of the Old Kingdom," Roberts noted, "and that literature is in

the form of braggart autobiographies of officers, inscribed in their tombs,

and poetic incantations to ensure the dead king's eternal rebirth with the

gods."12

Erman had observed that "the full development of the literature

appears only to have been reached in the dark period which separates the Old

from the Middle Kingdom, and in the famous Twelfth Dynasty... It is the

writings of this age that were read in the schools five hundred years later,

and from their language and style no one dared venture to deviate. The feature

which, from an external standpoint, gives its character to this classical

literature ~ it cannot be called by any other name ~ is a delight in choice,

not to say far-fetched, expressions."13

Old Kingdom literature consisted primarily of creation myths,

religious hymns and prayers; heroic tales of gods and men triumphant; texts

dealing with life after death; legal treatises; historical accounts of

military conquest; records and accounts of agricultural, mining and other

labor activities; royal decrees; and, most famous of all, didactic literature

like the legendary treatise, The Instruction of the Vizier Ptahhotep,

an early Egyptian precursor of the Hebrew Book of Proverbs.

Yet, even during this golden era of Egyptian unity and power there was

an embryonic development of a new, more socially conscious, literature.

Breasted noted in The Dawn of Conscience the appearance in the third

millennium B.C., "for the first time historically what the modern

psychologists have concluded from their observations of the life of man as it

is found in modern times. I am referring to their conclusion that the moral

impulses of the life of man have grown up out of the influences that operate

in family relationships."

The Pyramid Texts, a collection of 4th and 5th Dynasty formulae for

furtherance of the afterlife, and didactic literature from both the Old and

Middle Kingdoms, extol the virtues of family and friends and reveal what

Breasted called "a much more highly developed stage of man's unfolding moral

life."14

Erman described the early Egyptians as "a gifted people,

intellectually alert, and already awake when other nations still slumbered;

indeed, their outlook on the world was as lively and adventurous as was that

of the Greeks thousands of years later...

""It is not to be wondered at that so gifted a people took a pleasure

in giving a richer and more artistic shape to their songs and their tales, and

that in other respects also an intellectual life developed among them ~ a

world of thought extended beyond the things of everyday and the sphere of

religion."15

Justice is a prevailing theme in the early literature, as revealed by

a 4th Dynasty tomb inscription as well as the Pyramid Texts. Ideas of justice

were associated with the great sun-god Re. The 6th Dynasty Instruction of

Ptahhotep represents the first known formulation of just conduct to be

found anywhere. Egyptians in the Old Kingdom believed in the use of common

sense and personal integrity. They prized worldly success as well as the wise

conduct of one's business affairs. Life itself centered almost wholly on

culture and power, but the early Egyptians were more kind, tolerant and

benevolent than those who followed, and some of their literature reflects

that, too. Of course, preparation for life after death was critically

important, as revealed most awesomely by the pyramids.

The citizens of Egypt were singularly devoted to their kings and to

building pyramids to perpetuate their immortality. Rainer Stadelmann, Director

of the German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo and a student of the Old

Kingdom, commented, "What held the Old Kingdom together was not so much a

belief in the divine nature of the king as a belief that through the king was

expressed the divine nature of society itself. Much later, after the fall of

the Old Kingdom, the people really believe in the importance of building a

pyramid. It's like a small town that builds a huge cathedral in the Middle

Ages. Faith is the spur."16

Of course our collection of Egyptian literature is by no means

complete, most of the surviving papyri having been discovered in tombs, where

the dry climate and structural protection preserved them. Only the most

important documents went with their owners to their graves; but that was

miraculous enough "seeing that the preservation of a literary work depends on

unlikely chance making it possible for a fragile sheet of papyrus to last for

three or four thousand years! Accordingly, out of a once undoubtedly large

mass of writings, only isolated fragments have been made known to us, and

every new discovery adds some new feature to the picture which we have painted

for ourselves of Egyptian literature."17

The early rise of a socially conscious literature was coincident with

the end of the pyramid age and the somewhat eroding omnipotence of the king.

The building of pyramids gave way to the erection of mortuary temples and

formulation of a more elaborate and refined funerary practice. Nevertheless,

such changes notwithstanding, it was a shattering blow to the people's faith

when the Old Kingdom collapsed. Pepi II, last known king of the Old Kingdom,

reigned for 90 years as Egypt tottered and fell. For years governors of local

nomes and a rising and growing priesthood had eroded the pharaoh's power and

undermined his authority. Furthermore, famine indicated the disfavor of the

gods. Nothing is really known of the First Intermediate Period; and, in fact,

some have theorized that the First and Second Intermediate Periods were one

and the same. At any rate, from the kings seated in Memphis, power shifted to

the rulers at Heracleopolis, where a feeble dynasty left little to testify to

its existence beyond a few monuments and three masterpieces of wisdom

literature: The Instruction Addressed to King Merikare, the

Instruction of Duauf, and the Protests of the Eloquent Peasant.

Amidst the general collapse of all that was so grand, a new early

Middle Kingdom outpouring of skeptical and pessimistic literature arose.

The Song of the Harp-Player suggests a life of indulgence and pleasure as

a means of coping with the dreariness and misery of life. The Tale of the

Eloquent Peasant tells of a poor man seeking (and being granted) justice

and compensation after being wronged. But saddest of all is A Dispute Over

Suicide in which the misanthrope, weary of life, his fortunes lost in the

general collapse, argues with his soul over whether or not to end it all. It

is a dilemma without hope. "It is remarkable," Breasted lamented, "that it

contains no thought of God; it deals only with glad release from the

intolerable suffering of the past and looks not forward."18

And Breasted went on: "Such were the feelings of some of the Egyptian

thinkers of the new age as they looked out over the tombs of their ancestors

and contemplated the colossal futility of the vast pyramid cemeteries of the

Old Kingdom." The skeptics doubted "all means, material or otherwise,

for attaining felicity or even survival beyond the grave. To such doubts there

is no answer; there is only a means of sweeping them temporarily aside, a

means to be found in sensual gratification which drowns such doubts in

forgetfulness."19

Egyptian writers had become more reflective of society and of life

itself. Some exhorted themselves and others to good deeds, wise conduct, and

noble hearts. Others, like the harp-player and the misanthrope, simply sank

deeper into despair. Yet those who urged noble aspirations and wise conduct

still failed to contrast in print their ideals with the realities of the

corrupt society in which they lived. Some, like the writer instructing

Merikare, noted the sins of individuals but somehow failed to enlarge their

observations to include the whole of society. By the late Middle Kingdom,

however, "the Egyptian sages have become fully aware of the glaring contrast

between the inherited ideals of worthy character and the appalling reality in

the society around them."

A priest of Heliopolis named Khakheperre-sonb, during the reign of

Sesostris II, expressed his somber musings on society in The Complaints of

Khakheperre-sonb. This composition was still in circulation and widely

read centuries later when the current copy was made on a writing board

(British Museum 5645). "It is of especial interest," Breasted observed, "as

indicating at the outset that such men of the Feudal Age were perfectly

conscious that they were thinking upon new lines, and that they had departed

far from the traditional complacency which characterized the wisdom of the

fathers."20

It was about the time of the 12th Dynasty that, as Breasted noted, "we

may discern a great transformation. The pessimism with which the men of the

early Feudal Age, as they beheld the desolated cemeteries of the Pyramid Age,

or as they contemplated the hereafter, and the hopelessness with which some of

them regarded the earthly life were met by a persistent counter-current in the

dominant gospel of righteousness and social justice set forth in the hopeful

philosophy of more optimistic social thinkers, men who saw hope in positive

effort toward better conditions."21

For the first time along the Nile men were awakened to the moral

depravity of the society in which they lived and wrote about it. To

assuage their despair over the collapse of general order there had previously

been no vision of better things to come, or of a Messianic ruler who would

rule with wisdom and benevolence; but soon there were men of vision who

dreamed of better things and said so. The Eloquent Peasant strived for it, and

in his story the need for a righteous ruler was therefore inferred but not

explicitly stated. It remained for others to express it, and among them ~ the

first on record that we know of ~ was the futuristic prophecy of the lector

priest Neferrohu to King Snofru in the famous Petersburg Papyrus (1116B).

Written by a scribe named Mahu, it concludes a long description of calamity

with these words spoken by the priest:

| "There is

a king shall come from the South, whose name is Ameny, son of a Nubian

woman, a child of Chen-Khon. He shall receive the White Crown; he shall

assume the Red Crown; he shall unite the Two Powerful Ones ["epithet of

the two goddesses, Buto and Nekhebt, who preside over the double crown"

ftnt. 3]; he shall propitiate Horus and Seth with what they love, the

Surrounder of fields' in his grasp, the oar... |

| "The

people of his time shall rejoice, (this) man of noble birth shall make his

name for ever and ever. Those who turn to mischief, who devise rebellion

shall subdue their mouthings through fear of him. The Asiatics shall fall

by his sword, the Libyans shall fall before his flame, and the rebels

before his wrath, and the froward (sic) before his majesty. The Uraenus

that dwelleth in front shall pacify for him the froward. |

| "There

shall be built the 'Wall of the Prince,' so as not to allow the Asiatics

to go down into Egypt, that they may beg for water after (their) wonted

wise, so as to give their cattle to drink. And Right shall come into its

place, and Iniquity be cast (?) forth. He will rejoice who shall behold

and who shall serve the King. And he that is prudent shall pour to me

libation when he sees fulfilled what I have spoken. |

| "It has

come to a successful end. (Written) by the scribe [Mahu]." |

Gardiner called this predictive passage "the culminating point of a

pessimistic passage of the true prophetic type." And he and subsequent

Egyptologists believed the prediction to be of the coming of King Amenemhet I,

first king of the 12th Dynasty who ended the chaos and disorder of the First

Intermediate Period and who is also mentioned in the Story of Sinuhe as

the builder of the Wall of the Prince which was intended to fend off the

Bedouins and other nomadic invaders. The building of this wall not far from

the Wadi Tumilat in the eastern Delta was the culminating point of Neferrohu's

prophecy and was further proof of Gardiner's contention that "the period

between the Middle and New Kingdoms witnessed considerable and historical

Asiatic incursions into the fertile and therefore much coveted Valley of the

Nile."22

And finally there is the scribe whose lamentations came down to us as

The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage. Ipuwer was neither a pessimist nor

a fatalist. In The Development of Religion and Thought in Ancient Egypt

Breasted observed, "There were men who, while fully recognizing the corruption

of society, nevertheless dared dream of better days. Another moral prophet of

this great age has put into dramatic setting not only his passionate

arraignment of the times, but also constructive admonitions looking toward the

regeneration of society and the golden age that might ensue." The

Admonitions, Breasted maintained, is "perhaps the most remarkable document

of this group of social and moral tractates of the Feudal Age...

"We must regard the Admonitions of Ipuwer and the Tale of the Eloquent

Peasant as striking examples of such efforts, and we must recognize in their

writings the weapons of the earliest known group of moral and social

crusaders."23

What inspires this Messianic linkage is Ipuwer's longing, late in his

lamentations after describing the holocaust and then blaming it on the king,

for an ideal ruler like the sun-god Re who "brings coolness upon heat; men

say: 'He is the herdsman of mankind, and there is no evil in his heart.'

Though his herds are few, yet he spends a day to collect them, their hearts

being on fire (?). Would that he had perceived their nature in the first

generation; then he would have imposed obstacles, he would have stretched out

his arm against them, he would have destroyed their herds and their

heritage... Where is he today? Is he asleep? Behold, his power is not seen"

(11,13-12,6).

The phrase "He is the herdsman of mankind" in verse 12,1 is

significant. Breasted commented, "The Sun-god is called 'a valiant herdman who

drives his cattle' in a Sun-hymn of the Eighteenth Dynasty, and this, it seems

to me, makes quite certain Gardiner's conclusion (on other grounds) that this

passage is a description of the reign of Re."24

Furthermore, John Van Seters pointed out that the view of the king as

the herdsman of his people was a late development unknown before the 12th

Dynasty.25

This passage elevates Ipuwer's prophecy in the Admonitions

above Neferrohu's in the Petersburg Papyrus because Neferrohu prophesied the

coming of an earthly king in the more or less immediate future while Ipuwer

longed for the benevolent reign of the sun-god in an idyllic heaven on earth.

It is worth recalling that the sun-god Re was the source of justice in the Old

Kingdom; and this passage, cited by Breasted as the most important and

illuminating in the entire text, brings to mind the righteous reign of King

David in Israel. Ipuwer appears to be confronting the king in precisely the

same manner in which the prophet Nathan will later confront King David after

the adultery with Bathsheba by pointing his finger at the king and declaring,

"You are the man!" This similarity, by the way, was not lost on Gardiner, who

nevertheless denied the prophetic nature of the text.

"Lange first called attention to the Messianic character of this

passage," Breasted continued. "His interpretation, however, was that the

passage definitely predicts the coming of the Messianic king. Gardiner

has successfully opposed Lange's conclusion as far as prediction is

concerned... But no student of Hebrew prophecy can follow Gardiner in his next

step, viz., that by the elimination of the predictive element we deprive the

document of its prophetic character. This is simply to impart a modern English

meaning of the word prophecy as predictive into the interpretation of

these ancient documents, particularly Hebrew literature... (Gardiner) states

the 'specific problem' of the document to be 'the conditions of social and

political well-being.' This is, of course, the leading theme of Hebrew

prophecy. On the basis of any sufficient definition of Hebrew prophecy,

including the contemplation of social and political evils, and admonitions for

their amelioration, the utterances of Ipuwer are prophecy throughout."26

Gardiner believed the papyrus was originally composed during the 12th

Dynasty but that it described the chaos of the First Intermediate Period

separating the Old and Middle Kingdoms. "The spelling is, on the whole, that

of a literary text of the Middle Kingdom," Gardiner explained. He found

parallels to the Ramesseum text of Sinuhe and Middle Kingdom writing, some

instances of New Kingdom spellings and the New Kingdom method of "appending

the pronominal suffix to the feminine nouns...in swyt-f 7.13; hryt-f

10,1. The orthography of our text thus brings us to very much the same results

as its palaeography: the date of the writing of the recto cannot be placed

earlier than the 19th. dynasty, but there are indications that the scribe used

a manuscript a few centuries older."27

Erman later revealed that passages from the Admonitions which

recur in these two documents cited by Gardiner also indicate its date. Verses

from the Admonitions are "far more in place" in the Dispute Over

Suicide than in the Admonitions, and several verses from the

Admonitions found in the Instruction of Amenemhet are "interpolated

in a corrupt form" in the Instruction. "The Admonitions is thus

later than the Dispute of One Who is Tired of Life, and older than the

Instruction of Amenemhet."28 The Instruction, however, survives

~ except for the 18th Dynasty Papyrus Millingen which was copied in 1843 and

subsequently lost ~ only in schoolboy exercises on wooden tablets from the

19th Dynasty which are riddled with errors, a few fragments of papyrus, and

numerous ostraca from the New Kingdom; and, as we shall see, there are

numerous indications for a later date for the Admonitions than for the

Instruction.

Lange and Gardiner both assumed that the text was directed toward some

king who was to blame for the suffering of his people. In common with Sethe,

Gardiner saw it as an admonition on great social changes. Therefore, in spite

of the graphic nature of Ipuwer's descriptions of what he saw, it was not

until Velikovsky read it that it was seen as "the Egyptian version of a great

catastrophe."29

In 1964 Van Seters published his commentary on the Admonitions

in The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, which published Reginald

Faulkner's complete translation the following year. Van Seters recognized that

"the Admonitions doubtless reflects a very troubled period in Egypt's

history, and this logically offers the alternatives of the First and Second

Intermediate Periods...

"The events are described in such a way as to appear quite

contemporaneous with the author himself, and if this is the case one would

certainly expect the text to reflect at least the language of the Old Kingdom.

On the other hand, it is difficult to see how the many intimate connexions

with the Middle Kingdom can all be considered as anticipation. There is, in

fact, a more acceptable alternative which does full justice to the matter of

the orthography and language. This is a date late in the Thirteenth

Dynasty."30

Van Seters himself provided a deep historical understanding of the

text, since the Second Intermediate Period and the Hyksos takeover are

specialties of his. Like Velikovsky, he saw the Admonitions as a

description of a great calamity, though certainly not a cosmic one; and by

establishing the 13th Dynasty as the proper time slot for the Admonitions,

he ended decades of misdating. "Since the time of A. H. Gardiner's study of

the Admonitions of Ipuwer in 1909," he explained, "there has been a

general consensus among scholars that the work was written in, or at least

reflects, the First Intermediate Period in Egypt. However, the general

observations made by Gardiner himself relating to the problem of dating

certainly do not inspire a firm conclusion on the matter."31

More than half a century elapsed between Gardiner's translation of the

Admonitions and its study by Van Seters and Faulkner. "In the

interval," Faulkner commented, "our knowledge of Egyptian grammar and

vocabulary has greatly increased, thanks very largely to the work of Sir Alan

himself, with the result that, though his interpretation of the text as a

whole endures, there are passages where in the light of current knowledge some

advance can be made on the original English version."32

In establishing the historical context of the writings, Van Seters

noted Ipuwer's use of sttyw, a Middle Kingdom term to denote

Asiatics that was very rare in earlier texts. [To the Egyptians, all peoples

beyond their northeast frontier were "Asiatics."] Furthermore, sttyw

includes a character designating archers, a derivation of stt, "to

shoot." The term pdtyw generally designates "foreign bowman," a

Middle Kingdom term associated frequently with Asiatics, though not an ethnic

term as such. A third term, h3styw, meaning simply "foreigners,"

was applied in the Middle Kingdom particularly to Asiatics. Beginning in the

Middle Kingdom, however, the term hk3 h3s(w)t for foreigners was

definitely applied to Asiatics. The term h3styw, used by Ipuwer, refers

to Asiatics and was appropriate only to the Second Intermediate Period between

the Middle and New Kingdoms. There was frequent trade between Egypt and

Palestine during the Middle Kingdom, but very little contact during the Old

Kingdom. And the term wr for "foreign rulers," used by Ipuwer, does not

appear in Egyptian literature until the 13th Dynasty.

Interestingly, Ipuwer frequently referred to slaves; and, as Van

Seters pointed out, "The institution of slavery, apart from a type of serfdom

associated primarily with royal land estates, is not attested in the Old

Kingdom. It is, at the earliest, a product of the Middle Kingdom..." Not only

that, but "the terminology of slavery points to a social development which is

of late Middle Kingdom date."33

Ipuwer makes mention many times of the loss of the royal Residence, to

which Van Seters commented, "In these passages the author is speaking of the

present or the very immediate past when the Residence of the king was a

reality."34

The Residence (hnw) was identified by William C. Hayes

as "the common designation for Itj-towy in the Middle Kingdom" and "this

remained the capital of the Egyptian kings until the Hyksos overthrew it.

According to this alternative the Admonitions would portray the rise of

the Hyksos of the Fifteenth Dynasty and be very nearly contemporary with it."

Itj-towy was the Diospolis of Manetho or, in other words, Thebes.

Against the notion that the text is a predictive prophecy, Van Seters

noted that "the reprimand of the king makes sense only if Ipuwer is referring

to well-established dogmas, not just anticipating them, and the view of the

king as a 'herdsman' to his people expressed in the passage 11:11f. is a dogma

of the Middle Kingdom. The view of the king's relation to his people was so

entirely different in the Old Kingdom that Ipuwer's appeal to the king would

have fallen on deaf ears. There is, in fact, nothing in the Admonitions

which reflects the view of royalty in the Old Kingdom."35

This brings up the concept of freedom of speech, a concept nearly

unknown in antiquity. According to the Dictionary of the History of Ideas,

"the final impression is that in the crisis of the Old Kingdom freedom of

speech became an issue. Writers were aware that protesting, debating, and

accusing were ways of undermining the existing order. Silence appeared to be

the remedy: it became a central virtue in later days. It did not necessarily

mean compliance and obedience; it included an element of astuteness and

perhaps of concealment. But it implied the essential acceptance of an

unmodifiable order. The prospects of freedom of speech had never been

brilliant, because there was no institution to which potential reformers could

turn when they felt dissatisfied with the Pharaonic administration. There was

no regular assembly in which to voice discontent."

Certainly there had been advisers to kings and court officials since

the dawn of Pharaonic Egypt, but to question the Pharaoh was deemed

destructive to the established order. Therefore, what protests there were ~

the suicidal misanthrope, the harp-player ~ protested the futility of life but

never directly criticized the king. Ipuwer is the first sage on record to

directly confront the king with the misery he may have caused. After

describing rebellion and loose tongues all around him, "the Sage Ipu-wer

himself takes advantage of the freedom of speech he notices as a bad symptom

in the maidservants. He blames the king. He compels him to defend himself and

concludes by saying that what the King has done, though perhaps good, is not

good enough."36

The setting of the papyrus perfectly matches the situation leading up

to the Exodus. The downfall of the Middle Kingdom began at its inception.

Cyril Aldred in 1961 harkened back to the First Intermediate Period (to which

he, in common with everybody else at the time, assigned Ipuwer) and observed,

"With Egypt divided against itself, there was the inevitable immigration of

foreigners into the rich pastures of the Delta. Famine in their own lands

always drove Libyans and the wandering Semites of Sinai and the Negeb to graze

their flocks on the borders of the Delta in the manner of Abraham and

Jacob..."

Soon, however, these infiltrators were holding positions of

responsibility in Egypt. "Recent study of a papyrus in the Brooklyn Museum and

other documents has revealed that numerous Asiatics were in Egypt, perhaps

from the time of the First Intermediate Period, acting as cooks, brewers,

seamstresses, and the like. The children of these immigrants often took

Egyptian names and so fade from our sight. Asiatic dancers and a door-keeper

in the temple of Sesostris II are known, showing that these foreigners

attained positions of importance and trust. It is not difficult to see that by

the middle of Dynasty XIII, the lively and industrious Semites could be in the

same positions of responsibility in the Egyptian State as Greek freedmen were

to enjoy in the Government of Imperial Rome."37

Torgny Save-Soderbergh described the roller-coaster fortunes of

Egyptian regimes toward the end of the Middle Kingdom: "After the fall of the

Twelfth Dynasty...there followed a short period ~ let us say about a

generation ~ when the unity of Egypt was no longer upheld, but a number of

ephemeral kinglets ruled the country contemporaneously. However, Egypt soon

recovered its political unity and strength, and this passing weakness had not

changed Egypt's political position in the Near East."38

Two brothers, Neferhotpe and Sebkhotpe, brought Egypt back to power in

the 13th Dynasty, the former reigning for 11 years, the latter for at least

eight that we know of, and both leaving us abundant monuments to remind us

they were there.39 However, the renewed Egypt was not the same as it had been

before. Foreign ceramic ware is found in increasing numbers in Egyptian tombs.

"This ware and other goods," Save-Soderbergh pointed out, "bear witness to an

intense trade all over an immense area, a trade that was bound to modify to a

certain extent the character of the Egyptian civilization and to some extent

break down its conservative self-sufficiency, which is so typical of earlier

periods."

Time and the outside world were catching up with the dwellers of the

Nile. Egypt traded extensively with Byblos, in what is now Lebanon. Babel

under Hammurabi rose to power. The Kassites ruled in eastern, and the Hurrians

ruled in southwestern, Babylonia. After Sebkhotpe's reign ended, Egyptian

power declined again, and "later king-lists and the contemporary monuments

mention an overwhelming number of kinglets who must have reigned

contemporaneously. Egypt was again in a state more or less of anarchy, a ripe

fruit to be gathered by anyone with no great effort. At this time, and

possibly as a result of the unrest in Syria, Asiatics filtered into the Delta

and soon established themselves as local rulers there."40

Ipuwer complained that the Asiatics were well established in the

Delta. Since the time of Joseph the Hebrews had thrived in the land of Goshen

by the Wadi Tumilat, in the northeastern section of the Delta. If Velikovsky's

identification of the Hyksos as the Biblical Amalekites is correct ~ and it

certainly appears to be ~ then the Asiatics in the Delta were the Hebrews and

other scattered peoples from Asia Minor, and the Hyksos/Amalekites were on the

move from further north than the Delta because of the cosmic catastrophe

unfolding over all their heads. Having failed to defeat the newly freed

Israelites at Rephidim, they simply crossed Egypt's northern frontier when

that frontier was defenseless and picked on somebody a little less

troublesome.

Ipuwer stated that the Asiatics had been assimilated into the Egyptian

culture and held positions of authority. This, too, is in keeping with the

situation at the close of the Middle Kingdom. Although enslaved by this time,

the Hebrews and other semitic peoples had long been assimilated into the

Egyptian civilization, and some held positions of authority. From the early

second millennium B.C., Asiatic names, most of them household servants,

appeared in Egyptian records. The Brooklyn Papyrus alone, from the 13th

Dynasty reign of Sebekhotpe III, lists 79 household slave names of which 45

are northwest Semitic.41

Van Seters noted evidence of foreign workmen in the Faiyum of Kahun,

of slaves possessing a variety of skills, and of slaves engaged in mining

expeditions to the Sinai. Both groups, he pointed out, had "strong connexions

to the Eastern Delta," which is where Goshen was. But Semitic names were not

restricted to slaves. George Steindorff and Keith Seele observed of the Theban

13th Dynasty based at Itj-towy and the more obscure 14th Dynasty at Xois

[identified by Gardiner as "the modern Sakha in the central Delta"42]: "Both

dynasties consisted of innumerable rulers enjoying usually the briefest of

reigns. There is reason to believe that the throne lost its hereditary

character in the Thirteenth Dynasty and that elected kings of common origin

served for short terms, with the affairs of state controlled, for the most

part with vigor and stability, by a series of hereditary viziers. Some of the

kings left numerous monuments, large and small. A few of them bore Semitic

names, a plain token of the increasing Asiatic population which was

infiltrating the Delta and preparing the stage for that dire catastrophe

which...was to burst upon Egypt ~ conquest by the Hyksos."43

Ipuwer's lament that Asiatics had become assimilated into Egyptian

culture is also borne out by the fact that so many Asiatic slaves had Egyptian

names, many held government and religious positions, and some held positions

of authority, as Steindorff and Seele pointed out and as William A. Ward

demonstrated when he revealed that the Ugaritic personal name bn hnzr

was the Semitic original of the 13th Dynasty Egyptian royal name Hnjr,

a name borne by two obscure kings from that dynasty. "While the prenomens of

these kings are good Egyptian," Ward pointed out, "the name Hnjr is

not. The non-Egyptian origin of Hnjr has usually been accepted and the

correct Semitic original, h(n)zr 'swine,' has been known for many

years."44

Van Seters added, "Many of the foreign officials have good Egyptian

names, and, unless they are identified by the ethnic epithet c3m,

cannot be distinguished as foreigners. It is precisely this situation which

the writer of the Admonitions apparently laments."45

Donald Redford made an interesting point: "Ipuwer does not dwell on

the Asiatic threat to Egypt at length, but he does in fact mention their

presence within the land as a consequence of the weakness of the government.

'Lo, the face grows pale (for) the bowman is ensconced, wrong doing is

everywhere, and there is no man of yesterday ' (2,2)... 'Lo, the entire delta

is no longer hidden...foreign peoples are conversant with the livelihood of

the delta' (4, 5-8)."46 This was an ongoing situation to which Ipuwer and his

hearers had to be well accustomed. For several generations, perhaps even

centuries, the influx and infiltration of too many foreigners and foreign

influences had weakened the fabric of Egyptian society and diminished the role

and power of the government. It was a situation that would be repeated in

Jerusalem under the liberal reign of King Solomon and again in Egypt during

the narcissistic reign of Akhnaton.

Ipuwer bewails the fact that the northeast frontier is open to

invaders: "Indeed, the Delta in its entirety will not be hidden, and Lower

Egypt puts trust in trodden roads. What can we do?" (4,5). In former times the

Egyptians fortified this frontier most adequately, but now its defenses had

broken down. There was much traffic through this area in the late Middle

Kingdom, and the terrible holocaust described by Moses and amplified by

Velikovsky would have certainly rendered these fortifications useless.

Erman added, "The natural protection of the Delta afforded by its

swamps and lakes is no longer of any avail, the foreigners enter it in bands

and practise its crafts themselves. It is to be borne in mind that the Delta

in the later periods of Antiquity and during the Middle Ages was the centre of

industry and export. Such may well have been the case also at this earlier

date."47

Finally, Ipuwer blames the overthrow of his kingdom on both Asiatics

and Egyptians alike. Egyptians in the Middle Kingdom hired foreigners to serve

as frontier police. It apparently worked well on Egypt's southern frontier,

but in the north the frontier police appear to have collaborated with the

Asiatics in that Asiatics had assumed greater and greater administrative

control over the northern regions and used Egyptian officials.48

To echo Save-Soderbergh, Egypt was ripe for plucking.

* * * * *

Velikovsky's views of the Exodus, the plagues, and the Papyrus Ipuwer

were first stated in his Theses for the Reconstruction of Ancient History

in 1945:

|

4. The Egyptian and Jewish histories, as they are written, are

devoid of a single synchronism in a period of many hundreds of years.

Exodus, an event which concerns both peoples, is presumably not mentioned

in the Egyptian documents of the past. The establishing of the time of the

Exodus must help to synchronize the histories of these two peoples. |

|

5. The literal meaning of many passages in the Scriptures which

relate to the time of the Exodus, imply that there was a great natural

cataclysm of enormous dimensions. |

|

6. The synchronous moment between the Egyptian and Jewish histories

can be established if the same catastrophe can also be traced in Egyptian

literature. |

|

7. The Papyrus Ipuwer describes a natural catastrophe and not

merely a social revolution, as is supposed. A juxtaposition of many

passages of this papyrus...with passages from the Scriptures dealing with

the story of the plagues and the escape from Egypt, proves that both

sources describe the same events. |

|

8. The Papyrus Ipuwer comprises a text which originated shortly

after the close of the Middle Kingdom; the original text was written by an

eyewitness to the plagues and the Exodus. |

|

15. The Israelites left Egypt a few days before the invasion of the

Hyksos (Amu).49 |

In many of these points Velikovsky was correct, but in some he erred.

Ipuwer must have witnessed the plagues, because everybody in Egypt did;

but Ipuwer did not describe them.

The king to whom Ipuwer supposedly addressed his admonitions is

thought to have been Dedumesiu I, the 33rd (or 34th) king of the 13th Dynasty,

according to Theban monuments found at Thebes, Gebelein, and Deir el-Bahri. It

could be that this is the same king as Tutimaeus, of whom the third century

B.C. Egyptian priest Manetho wrote:

| "In his

reign, for what cause I know not, a blast of God smote us; and

unexpectedly, from the regions of the east, invaders of obscure race

marched in confidence of victory against our land. By main force, they

easily seized the rulers of the land, they then burned our cities

ruthlessly, razed to the ground the temples of the gods, and treated all

the natives with a cruel hostility, massacring some and leading into

slavery the wives and children of others."50 |

This description by Manetho ~ if it was correctly left to us ~

perfectly fits the conditions described by Ipuwer. The 13th Dynasty may not

have come to a complete termination with the invasion, however. Nicolas Grimal

has pointed out that it continued to wield only local power under the Hyksos

rule, although it eventually died out altogether.51

The drama begins when Moses goes before the pharaoh and says, "Thus

says the Lord, 'Let My people go!'"

The pharaoh refuses, and thus follow the plagues: the river turning to

blood, frogs throughout the land, gnats everywhere, a swarm of flies,

pestilence on the livestock, boils breaking out in sores on the people, the

hail stones (not ice, as is often believed, but hot stones) mingled with fire,

locusts to devour the crops and foliage, a dense and prolonged darkness, and

finally the death of the first-born by the hand of the Lord. The pharaoh tells

Moses to take his people and go away, and Moses takes the nation of Israel ~

its men, its women, its children, its flocks, its livestock, and even

proselytized Egyptians ~ and leaves the land of their sojourn. Along the way

they take with them Egyptian spoils: silver, gold and clothing.

The pharaoh then changes his mind and pursues the Israelites with all

his chariotry to Pi-hahiroth, where the most dramatic miracle of them all, the

parting of the Red Sea, gives the Israelites an avenue of escape. The

Egyptians pursue them across the seabed, only to be trapped and engulfed when

the waters collapse. Whether or not the king goes with them, the entire

military force of the Theban 13th Dynasty disappears in a seething whirlpool.

In the desert the Israelites defeat the Hyksos/Amalekites at Rephidim

and both groups go their separate ways: the Israelites heading south to wander

in the desert for 40 years while the Hyksos/Amalekites go west and sweep down

into a defenseless Egypt. It is at precisely this point in the sequence of

events that Ipuwer picks up the narrative.

For this analysis, Reginald O. Faulkner's 1965 translation of the

Papyrus Ipuwer will be used. A parenthetical reference, for example "(7,2),"

designates the page and line, as in "Page 7, Line 2."

As already stated, the beginning of the papyrus is lost. Unlike the

Petersburg Papyrus 1116B in which Mahu recorded Neferrohu's prophecy, we don't

know what prompted Ipuwer to take up pen in hand, for what specific purpose,

or to which specific king. The situation described by him gave him an ample

subject matter to record, to be sure, and it was surmised that he was

addressing the king on whose shoulders he was placing the blame for Egypt's

woes. If Dedumesiu/Tutimaeus was the Pharaoh of the Exodus, and if he

perished in the Red Sea, then he was not the king Ipuwer addressed. Perhaps

Ipuwer addressed one of the following provincial 13th Dynasty rulers Grimal

mentioned. This will be addressed again later.

Ipuwer begins his lamentations with a general description of the

rebellion and Egypt's distress: "The door-keepers say: 'Let us go and

plunder'. The confectioners... The washerman refuses to carry his load... The

bird-catchers have drawn up in line of battle... The inhabitants of the Delta

carry shields. The brewers...sad. A man regards his son as his enemy.

Confusion...another. Come and conquer; judge...what was ordained for you in

the time of Horus, in the age of Ennead...52 The virtuous man goes in mourning

because of what has happened in the land...goes...the tribes of the desert

have become Egyptians everywhere.

"Indeed, the face is pale; ...what the ancestors foretold has arrived

in fruition..." (1,1).

The plagues have already devastated the land, the Israelites have

escaped across the Red Sea, and the Hyksos/Amalekites have entered Egypt in

their brutal lust for blood and conquest. The government has been overthrown

and the rich have been despoiled: "Indeed, poor men have become owners of

wealth, and he who could not make sandals for himself is now the possessor of

riches" (2,4).

There is violence and mass slaughter: "Indeed, hearts are violent,

pestilence is throughout the land, blood is everywhere, death is not lacking,

and the mummy-cloth speaks even before one comes near it" (2,5-6).

"Blood is everywhere" was likened by Velikovsky to the Nile turning to

blood, but the context here is of blood from the overall slaughter. "Indeed,"

Ipuwer adds, "many dead are buried in the river; the stream is a sepulchre and

the place of embalmment has become stream" (2,6).

It is a time of revolution: "Indeed, noblemen are in distress, while

the poor man is full of joy. Every town says: 'Let us suppress the powerful

among us'" (2,7-8).

Now comes the famous verse which Velikovsky interpreted as the earth

rolling over on its terrestrial axis: "Indeed, the land turns round as does a

potter's wheel; the robber is a possessor of riches and the rich man is become

a plunderer" (2,9).

Gardiner interpreted the phrase "the land turns round as does a

potter's wheel" as meaning that "the social order is reversed, so that slaves

now usurp the places of their former masters," and "he who was once a robber

is now rich, and he who was formerly rich is now a robber."53

Breasted agreed with Gardiner, noting that "In the longest series of

utterances all similarly constructed, in the document, the sage sets forth the

altered conditions of certain individuals and classes of society, each

utterance contrasting what was with what is now."54

Given the context in which the line is found, Gardiner's

interpretation appears to be correct, and one would also have to wonder how an

Egyptian scribe in the midst of a terrible calamity would be aware that the

planet was rolling over on its axis. However, the question cannot be dismissed

so easily. In Worlds in Collision, Velikovsky wrote, "This papyrus

bewails the terrible devastation wrought by the upheaval of nature. In the

Ermitage Papyrus [Petersburg 1116b recto] also, reference is made to a

catastrophe that turned the 'land upside down; happens that which never (yet)

had happened.' It is assumed that at that time ~ in the second millennium ~

people were not aware of the daily rotation of the earth, and believed that

the firmament with its luminaries turned around the earth; therefore, the

expression, 'the earth turned over,' does not refer to the daily rotation of

the globe."55

The Ermitage Papyrus (1116B recto) containing Neferrohu's prophecy,

quoted earlier and above, also declares, "I show thee the land upside down;

that happens which never happened before. Men shall take up weapons of war;

the land lives in uproar. All good things have departed."56

This sounds like an echo of Ipuwer's lament, but Velikovsky had

another ace up his sleeve: "Nor do these descriptions in the papyri of Leiden

and Leningrad leave room for a figurative explanation of the sentence,

especially if we consider the text of the Papyrus Harris ~ the turning over of

the earth is accompanied by the interchange of the south and north

poles...

"The Magical Papyrus Harris speaks of a cosmic upheaval of fire and

water when 'the south becomes north, and the Earth turns over.'"57

In the tomb of the general and king Horemhab, supposed 18th Dynasty

successor to Tutankhamen, is a stela containing a relief depicting him

worshiping three deities: Harakhte, Thoth, and Mat. Over Re, the sun-god,

these words are inscribed: "Harakhte, only god, king of the gods; he rises

in the west, he sendeth his beauty ~ ~" (emphasis added).58

On this inscription, Velikovsky commented, "Harakhte is the Egyptian

name for the western sun. As there is but one sun in the sky, it is supposed

that Harakhte means the sun at its setting. But why should the sun at its

setting be regarded as a deity different from the morning sun? The identity of

the rising and the setting sun is seen by everyone. The inscriptions do not

leave any room for misunderstanding...

"The texts found in the Pyramids say that the luminary 'ceased to live

in the occident, and shines, a new one, in the orient.'"59

The ancients were well aware of the roundness of the earth, something

Moses would have learned as a boy attending Egyptian schools, and they were

excellent and accurate astronomers. It is therefore puzzling ~ not to mention

mystifying to uniformitarians who assume that nothing in the solar system has

changed for millions of years ~ that the ceiling in the tomb of Hatshepsut's

architect, Senmut, contains a panel showing the celestial sphere with the

constellations and signs of the zodiac in what Alexander Pogo called "a

reversed orientation." In other words, it is a mirror image ~ i.e., exactly

reversed ~ of the southern sky today.

Pogo noted that a "character-istic feature of the Senmut ceiling is

the astronomically objectionable orientation of the southern panel; it has to

be inspected, like the rest of the ceiling, by a person facing north, so that

Orion appears east of Sirius...

"The list of the decans pre-ceding the Sah-Sepdet in the tradi-tional

arrangement are listed in the western part. The southern strip of the

Ramesseum, like the southern panel of Senmut, must be read in the temple, by a

person facing north. On the ceiling of Seti I, on the other hand, the

orientation of the southern panel is astronomically correct, so that Orion

precedes Sirius in the westward motion of the southern sky.

"The irrational orientation of the southern panel has caused some

confusion in the representation of Sah on the ceilings of Senmut and of the

Ramesseum, both of which obviously follow the same tradition. On the ceiling

of Seti I ~ which reflects another tradition ~ Osiris-Sah, participating in

the nightly westward motion of the sky, is running away from Isis-Sepdet...

With the reversed orientation of the south panel, Orion, the most conspicuous

constellation of the southern sky, appeared to be moving eastward, i.e., in

the wrong direction... The Senmut and the Ramesseum ceilings represent Orion

in the <<reversed>> position..."

And Pogo, referencing the 20th century sky, observed that "Mythologically,

both the Senmut-Ramesseum and the Seti traditions may be equally valuable;

astronomically, the Seti representation is far more satisfactory."60

Pogo and his uniformitarian brethren never understood how ancient

astronomers could not have been aware that the sun had "always" risen in the

east and set in the west; but Velikovsky commented, "The end of the Middle

Kingdom antedated the time of Queen Hatshepsut by several centuries. The

astronomical ceiling presenting a reverse orientation must have been a

venerated chart, made obsolete a number of centuries earlier." And "the

southern panel shows the sky of Egypt as it was before the celestial sphere

interchanged north and south, east and west. The northern panel shows the sky

of Egypt as it was on some night of the year in the time of Senmut."61

Gardiner's interpretation of the Ipuwer verse might be favored over

Velikovsky's, but there are the Magical Papyrus Harris, the inscription in

Horemhab's tomb, and the panel in Senmut's mortuary, to consider. It is also

worth noting that ancient literature abounds with references to the sun

reversing its direction in the sky. Plato in Statesman and Laws,

Euripides in Electra and Orestes, Senaca in Thyestes, and

Caius Julius Solinus in Polyhister, among others, all mention a time

when the sun rose in the west before changing its direction to rise in the

east.

This westward rising had serious ramifications. Hans S. Bellamy noted

that "The Aztecs regarded the west as the chief cardinal point. We regard the

east as the most impor-tant direction, chief because the sun rises there. The

sunset cannot have been the reason for their 'occidation'...

"The Chinese say that it is only since the new order of things has

come that the stars move from east to west. After the breakdown of the

Tertiary satellite the shooting-star streams had rushed over the heavens from

west to east. It should also be noted that the signs of the Chinese zodiac

have the strange peculiarity of proceeding in a retrograde direction, that is,

against the course of the Sun."62

In Ugarit (Ras Shamra), a poem dedicated to the planet-goddess Anat

credits her as the one who "exchanged the two dawns and the position of the

stars."63 Mexican hieroglyphics mention "four historic suns" as four world

ages with shifting cardinal points.64 The Mexicans pictured the sun's reversal

as a heavenly ball game amidst upheavals and earthquakes on earth. The Eskimos

in Greenland recalled a time in the distant past when the earth rolled over

and its people became antipodes.65 The Tractate Sanhedrin of the Talmud

declares, "Seven days before the deluge, the Holy One changed the primeval

order and the sun rose in the west and set in the east."66

Velikovsky explained that these and other sources do not all point

toward the same event. Herodotus, who derived his information from the priests

in Egypt, counted four reversals of the rising sun: "The sun, however, had

within this period of time, on four several (sic) occasions, moved from his

wonted course, twice rising where he now sets, and twice setting where he now

rises."67

What this all means is that, in the ancient but historical past ~ that

is, within the memory of the human race, and on one or more occasions ~ the

rising sun reversed its direction, and Velikovsky maintained that Ipuwer was

referring to this.

Meanwhile, the slaughter continues. Ipuwer looks out at the Nile and

writes, "Indeed, the river is blood, yet men drink of it. Men shrink from

human beings and thirst after water" (2,10).

Velikovsky believed this referred to the first plague, when Moses

touched his staff to the water and the Nile turned to blood. And, on the

surface, it could have, but the context here is of the bloody slaughter

throughout the land during the conquest. There have been recorded instances in

battle of rivers and streams running red with the blood of fallen soldiers.

Ipuwer's description of the Nile as blood could sound figurative and yet

describe a real phenomenon. During the Battle of Loos in Belgium during the

First World War, the British Y Company received orders to jump off a point

which was at the top of a small hill. At the bottom of the hill was a creek

about five yards wide. As Y Company advanced, a German machine gun opened up

on them, and the slaughter was on before the soldiers even came close to the

stream. In all, 3,519 men were wounded or lost their lives to pay for 300

yards of mud, a typical bargain in the War to End All Wars. However, a unique

feature in this battle was the stream. Quarter Master Sergeant R. S. McFie of

the Lincolnshire Battalion recalled in his diary,

| "The

German machine guns started in right off and the entire first line of our

charge went down like nine pins. It was hard to make your way over them in

some places. Once we got to the stream it got worse if that were possible.

It was hardly a foot deep and hardly no banks. But there were bodies

everywhere... |

| "I don't

know how we survived when I looked back in the little brook. It was jammed

full of us. The water was... It looked like something coming from a

slaughterhouse it was so red. Later someone said a man could have walked

on it the blood was so thick. Later I found it was worse than I thought.

The regiment was practically wiped out."68 |

Ipuwer has already informed us that bodies were buried in the river,

possibly because, as Erman surmised, "The corpses are too numerous to be

buried. They are thrown into the water like dead cattle."69

But there are more grizzly things to come: "Indeed, crocodiles are

glutted with the fish they have taken, for men go to them of their own accord"

(2,12). Gardiner commented, "The crocodiles have more than enough to feed

upon; men commit suicide by casting themselves into the river as their

prey."70 As to men drinking the water, Erman's translation of the verse makes

it clearer: "Nay, but the river is blood. Doth a man drink thereof, he

rejecteth it as human, (for) one thirsteth for water."71

It is also known that men who commit savage acts (i.e., cannibalism,

drinking blood, etc.) don't hang around other people and brag about it; the

inherent shame or the necessary depression or mental aberration makes them

more reclusive. Whatever it was that Ipuwer had in mind, it is still hard to

square the overall context of these lines with Velikovsky's synchronization of

the verse with the first plague.

Death is everywhere: "Indeed, men are few, and he who places his

brother in the ground is everywhere" (2,13).

The land has been devastated, first by the plagues and then by the

conquering hordes: "Indeed, the desert is throughout the land, the nomes are

laid waste, and barbarians from abroad have come to Egypt" (3,1).

The phrase "barbarians from abroad" could refer to the Hyksos sweeping

into Egypt suddenly from beyond its northeastern frontier, and not simply as

long-standing residents who gradually took over. In fact, the entire papyrus

describes a sudden and bloody conquest, not the gradual infiltration most

Egyptologists prefer. Ipuwer's references to shepherd-kings are also new; no

such kings were referred to in any of the previous late Middle Kingdom

documents which abound with references to Asiatics living and prospering in

Egypt. And his description of desert throughout the land and nomes being laid

waste is ample evidence of the massive destruction wrought by the plagues,

since a mere conquering army could not have caused it.

All commerce has ceased: "None indeed sail northward to Byblos

today... They come no more; gold is lacking...and materials for every kind of

craft have come to an end. The...of the Palace has been despoiled. How often

do the people of the oases come with their festival spices, mats and skins,

with fresh rdmt-plants, grease of birds...

"Indeed, Elephantine and Thinis(?) [are in the series(?)] of Upper

Egypt, (but) without paying taxes owing to civil strife. Lacking are grain

(?), charcoal, irtyw-fruit, m3rw-wood, nwt-wood, and

brushwood. The work of the craftsman [...] are the profit(?) of the Palace. To

what purpose is a treasury without its revenues?... That is our fate

and that is our happiness! What can we do without it? All is ruin!"

(3,11-13).

Velikovsky likened these last lines to the loss of fish in the river

and grain in the fields due to the plagues, but Ipuwer here appears to be

talking about the stuff of commerce from foreign trade. With no import or

export, revenues dried up and everyone suffered.

Ipuwer goes on to describe the misery around him: "Indeed, laughter

has perished and is no longer made; it is groaning itself that is throughout

the land, mingled with complaints... Indeed, great and small say: 'I wish I

might die.' Little children say: 'He should not have caused me to live.'

"Indeed, the children of princes are dashed against walls, and the

children of the neck (perhaps "the equivalent of our 'children in arms'"72)

are laid out on the high ground" (7,13-14,3).

The verse about children being dashed against walls, and a later verse

about the children of princes being laid out in the streets (6,12), were

interpreted by Velikovsky as referring to the tenth plague, which was a time

of earthquake and storm as well as the death of the first-born.73 The context,

however, would appear to be that of children being slaughtered during the

invasion and revolt, at which time the Israelites were long gone into the

desert.

"Indeed, that has perished which yesterday was seen, and the land is

left over to its weakness like the cutting of flax" (4,5). This could be

figurative, referring to the world Ipuwer knew, but it probably refers to the

devastation wrought by the plagues and the subsequent invasion. But, suddenly

in the midst of his lamentations, Ipuwer bewails "...because of noise; noise

is not...in years of noise, and there is no end to noise" (4,1-2). Gardiner

could make no sense of this, but Velikovsky felt the entire cosmic cataclysm

was responsible for such horrendous noise, and that could very well be the

case.

Ipuwer describes female slaves who are free with their tongues and

irked by orders from their mistresses, men knowing right but doing wrong,

animals' hearts weeping and cattle moaning, and people going hungry for lack

of food. "Would that there were an end to man," the scribe laments, "without

conception, without birth! Then would the land be quiet from noise and tumult

be no more" (6,1).

Egypt's records are destroyed and its secrets revealed: "Indeed, the

private council-chamber, its writings are taken away and the mysteries which

were in it are laid bare.

"Indeed, magic spells are divulged; smw- and shnw-spells

are frustrated because they are remembered by men" (6,5-7).

Erman explained of the magic spells, "Owing to their having become