The Field of Dreams

People Will Come!

By Henry Zecher

If you ever want a preview of heaven, not to mention a glimpse of all that was once good about America, go to Dyersville, Iowa, a sleepy little town just west of DuBuque, population 3,800, not counting the cows. You may have never heard of it, but nearly every one of you has seen it. And, if you haven't, you should. Here's why:

For nearly a century and a half, our national pastime was baseball. No game demands more precise athletic skill, more perfect timing, more intricate strategy. No game has ever epitomized so well the American spirit, or displayed so clearly the better parts of our human natures. It has been played in ball parks, sandlots and backyards, in the dreams of children and in the memories of old men. Film critic Joel Siegel called it "in many ways a metaphor for America, and for the American mythology. The pitcher against the batter ~ that's the gunfight at high noon."

One of our most popular folk songs ~ Take Me Out to the Ballgame ~ celebrates the atmosphere of the ballpark and the joy of the game. The only true American ballad ever written ~ Ernest Lawrence Thayer’s Casey at the Bat ~ dramatizes the thrill of the game and the town hero coming out to save the day and striking out.

Screenwriter Phil Dusenberry added, "It's individual achievement. You're out there for all the world to see, and you either go to glory or fall on your face, in full view of everyone. It represents the great American dream in lots of ways." Even poet Walt Whitman rhapsodized about the game: "I see great things in baseball. It's our game, the American game. It will repair our losses and be a blessing to us."

In spite of the popularity of football and the oncoming of basketball, annual attendance figures before the strike a few years ago proved that baseball was still the national pastime. The game appeared before the Civil War and gained popularity afterwards at a time when there were few other sports to rival it: football was just developing and for decades would be overcoming its violent image; boxing was at first illegal and still remained scandal-ridden well into the 20th century; and basketball hadn’t even been invented yet. Baseball was easy for any group of people to play: all you needed was a ball (or a rock, or even a bottle cap), a bat or a stick, and an empty lot. Even a street would do.

And finally, people were accustomed to long days of hard work. They who worked in factories and mills, and on farms, understood the slow pace and pains-taking intricacies of baseball, just as they understood what was then the world’s most popular sport on all seven continents ~ professional wrestling, at that time honest (at the championship level) and legitimate. But wrestling was universal. Baseball was purely American, and it uniquely captured the American spirit. Social commentator Jacques Barzun said half a century ago, "Whoever wants to know the heart and mind of America had better learn baseball."

To make a movie about so intricate a part of the American soul is no easy task. More than 100 times, Hollywood has gone to bat, and you can count on your fingers the times it’s done it right. But, good or bad, baseball movies have been about life, and they have depicted the best aspects of our nation's character.

Baseball was in show business long before Cecil B. DeMille, even before the World Series, which began in 1903. Thayer composed Casey at the Bat ~ the first true American ballad ~ in 1875, and actor DeWolfe Hopper (right, husband of gossipist Hedda Hopper) popularized the poem by reciting it on stage while the rest of us sat around waiting for Thomas Edison to invent Hollywood. Finally, in 1898, Edison filmed The Ballgame with two local amateur teams. Only a year later, he produced a comical version of Casey, which made Thayer more sorry than he already was that he'd ever written the poem in the first place.

Early films depicted human interest stories woven around baseball, like Elmer the Great (1933) about a Chicago Cub’s slugger who outwits gangsters and crooked pitchers to win the World Series. Then, in 1942, a new concept was introduced: the biographical motion picture, or biopic. The first and, most say, the best was Pride of the Yankees (1942), starring Gary Cooper as Lou Gehrig, the tragically stricken star of the New York Yankees. Other biopics followed: The Babe Ruth Story (1948) starring William Bendix as the Babe; The Stratton Story (1949) starring Jimmy Stewart as Monty Stratton, who lost a leg in a hunting accident, yet came back to pitch; The Jackie Robinson Story (1950) starring Robinson as himself; The Pride of St. Louis (1952) starring Dan Dailey as Dizzy Dean; The Winning Team (1952) with Ronald Reagan as Grover Cleveland Alexander; the dramatic Fear Strikes Out (1957) starring Tony Perkins as Jimmy Piersall, whose career was ended by insanity; The Babe (1992) with John Goodman taking his turn at bat as the immortal Ruth; and Cobb (1995) starring Tommy Lee Jones as the immortal Ty Cobb, arguably the greatest baseball player of them all.

There were, of course, the comedies: Whistling in Brooklyn (1944) with Red Skelton, It Happens Every Spring (1949) with Ray Milland; Kill the Umpire (1950) starring William Bendix; Major League (1989, followed by two sequels), with Charlie Sheen, Wesley Snipes, and Tom Berenger as members of an inept baseball team called the Cleveland Indians who defy their owner, who is trying to sell them as losers, by winning the pennant; The Rookie (1993) about a child with a freak arm who pitches in the major leagues; Mr. Baseball (1993), featuring Tom Selleck playing and cavorting in Japan; Rookie of the Year (1993), in which a freak accident transforms a young boy’s pitching arm into a major league winner; and Angels in the Backfield (1994) starring Danny Glover and featuring spiritual intruders in the ball parks.

There were musicals, including Take Me Out to the Ballgame (1949) with Gene Kelly and Frank Sinatra as semi-pro ballplayers who do vaudeville in the off season; and Damn Yankees (1958), a Broadway musical adaptation of Douglas Wallop's novel, The Year the Yankees Lost the Pennant, and starring Gwen Verdon, Tab Hunter and Ray Walston.

Baseball even entered the realm of horror with Robert DeNiro’s fearsome portrayal of The Fan (1996), a psychotic stalker who makes star player Wesley Snipes’s life a living hell; and it invaded science fiction in an X-Files episode, "The Unnatural," in which an old man informs Agent Mulder that a famous Negro League ballplayer was actually a Gray alien.

The greatest tribute to the game was Ken Burns’ eight-hour documentary, Baseball (1994), shown on the public broadcasting channels, and available on VHS and DVD.

But it was in 1973 that an entirely new focus emerged with the filming of Bang the Drum Slowly, starring Michael Moriarty and Robert De Niro in this moving story of a terminally ill ballplayer stricken with Hodgkins’ Disease. Suddenly, these movies were no longer about baseball players per se, but rather about individuals who happened to play baseball. It launched an entirely new genre in films: The Bad News Bears (1976), about an old broken-down former minor league pitcher (Walter Mathau) coaching a misbehaving little league team; The Bingo Long Traveling All-Stars and Motor Kings (1977) with Billy Dee Williams, James Earl Jones and Richard Pryor, about a barnstorming Negro baseball team who break from the league in 1939; Eight Men Out (1988) with John Cusack and Charlie Sheen, a marvelous telling of the 1919 Black Sox scandal; Bull Durham (1988) starring Kevin Costner and Susan Surandon, the first movie about the minor leagues; Penny Marshall's superb A League of Their Own (1992) with Tom Hanks, Geena Davis, and Madonna, looking back at the formation of the women's league during World War II; and, finally, For Love of the Game (1999), Kevin Costner’s third foray onto the cinematic playing field. Costner thus earned the distinction of having starred in three of the greatest baseball movies ever made.

Among the most heart-warming of baseball films, and the most artistic and uplifting, was The Natural (1984), based on the novel by Bernard Malamud and starring Robert Redford as Roy Hobbs, who was going to be the best there ever was until he was sidelined by a gunshot wound, and who returns 16 years later for one last stab at glory. Dusenberry, who wrote the screenplay, said, "The Natural is a truly tremendous American story." For cinematography and music alone, few movies of any kind have matched it, but more epic still was the story of a ballplayer who has one great season in the sun before hanging up his spikes."

Glenn Close played the female lead: "An integral part of the American dream is winning against the odds. The fact that he was struck down when he had his most potential, and then had the ability to come back and to succeed, to overcome these terrible adversities, and to become the great player that he wanted to be, makes it the true American dream."

The Natural might have remained the ultimate baseball movie of all time had Hollywood writer/director Phil Alden Robinson not been handed a book he was assured he would like. He doubted it. For one thing, it was about a farmer. Robinson was a city boy. For another, this farmer hears a voice and builds a baseball diamond in the middle of his cornfield. How imbecilic! And, after watching dumbfounded as ghosts of dead ballplayers come back to play on his field, he kidnaps the most prominent writer of the turbulent 60's and finally meets the long-dead father he had rejected in his youth. Like, let’s get real!

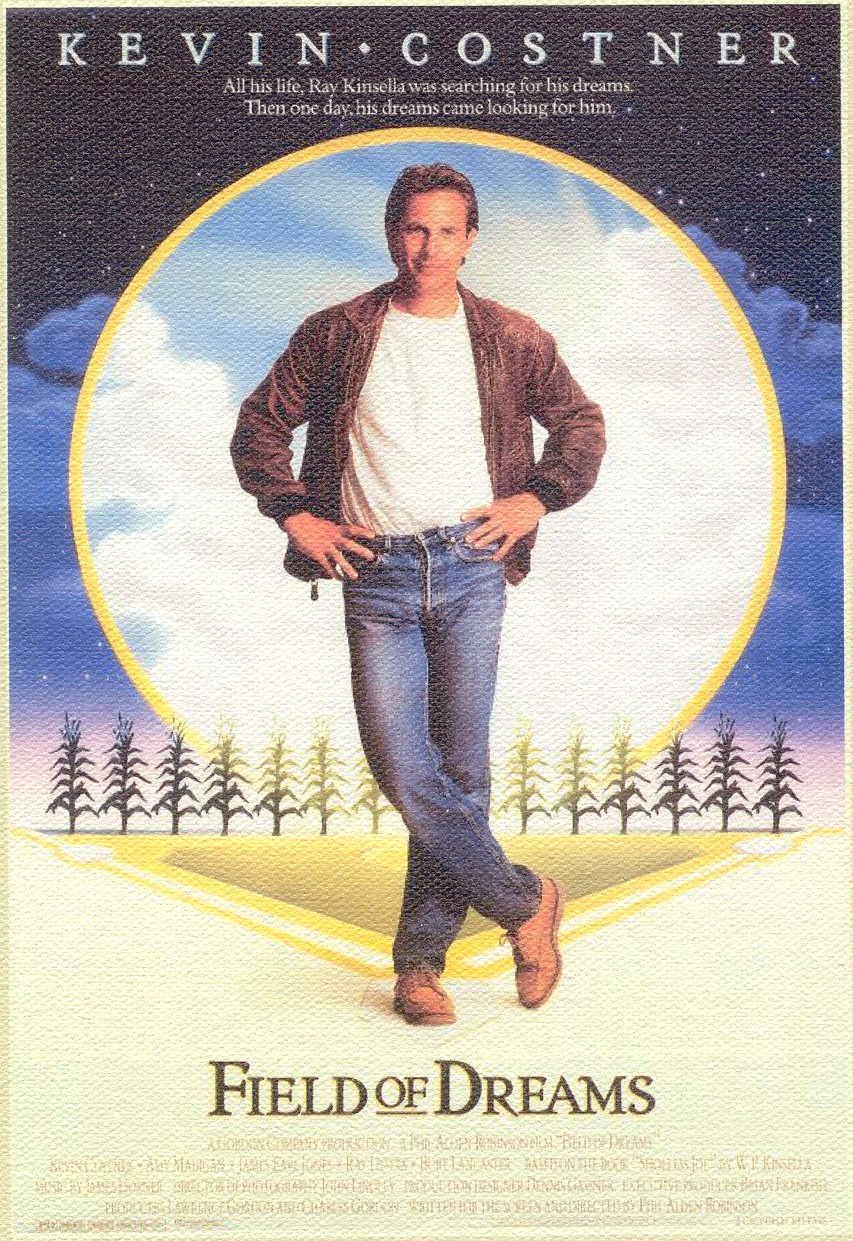

The book was Shoeless Joe, written by W. P. Kinsella, a graduate of the University of Iowa Writer's Workshop. Robinson read it, and he was hooked. He then went on to make the movie with Kevin Costner as Ray Kinsella, the farmer who built the diamond in the corn. The movie was filmed on a farm at 28963 Lansing Road, Dyersville, Iowa, and it was called Field of Dreams.

This is one of the greatest feel-good films of all time. The cast alone was stellar: Costner, James Earl Jones, Ray Liotta, Burt Lancaster, and Timothy Busfield. And no other movie has come as close to capturing, as this one did, what baseball is all about. As Jones put it, "the film was pure magic, a classic," and he called it "the most lyrical baseball movie of them all."

Sportswriter Frank Deford said, "Field of Dreams is absolutely, ultimately, totally, the baseball movie. It deals with everything about baseball, fathers and sons. It's a nostalgia. But baseball is not just sports, and it has much deeper roots and a much broader base, and can be analogous to so many more things, particularly the family."

This film deals with the real game of baseball, not the one played on playing fields, but what Jones called "the other, interior game of baseball, the game played in the fertile fields of the human imagination, the game that makes dreamers and story-tellers of us all."

With the game underway, Ray Kinsella is faced with a decision to sell the farm or be foreclosed; but writer Terence Mann (the J. D. Salinger character played by James Earl Jones, left) tells him, "People will come, Ray. They'll come to Iowa, for reasons they can't even fathom. They'll turn up your driveway, not even sure why they're doing it. They'll arrive at your door, as innocent as children, longing for the past. 'Of course, we won't mind if you look around,' you'll say. 'It's only $20 per person.' They'll pass over the money without even thinking, where it is money they have and peace they lack. And they'll walk out to the bleachers and sit in their shirt sleeves on a perfect afternoon, and they'll find they have reserved seats somewhere along one of the baselines, where they sat when they were children and cheered their heroes. And they'll watch the game and it'll be as if they've dipped themselves in magic waters. The memories will be so thick they'll have to brush them away from their faces. People will come, Ray."

No longer gazing out onto the field, the voice of the 60's turns to Ray: "The one great constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It's been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game, is a part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that once was good, and it could be again. Oh, people will come Ray, people will most definitely come.

And yet, this is not simply a baseball movie. This film is about second chances. Shoeless Joe Jackson, the legendary star of the Chicago White Sox, banned from baseball for life in 1919 with seven of his teammates for their part in the Black Sox scandal, returns with those teammates to play again. But that isn’t all.

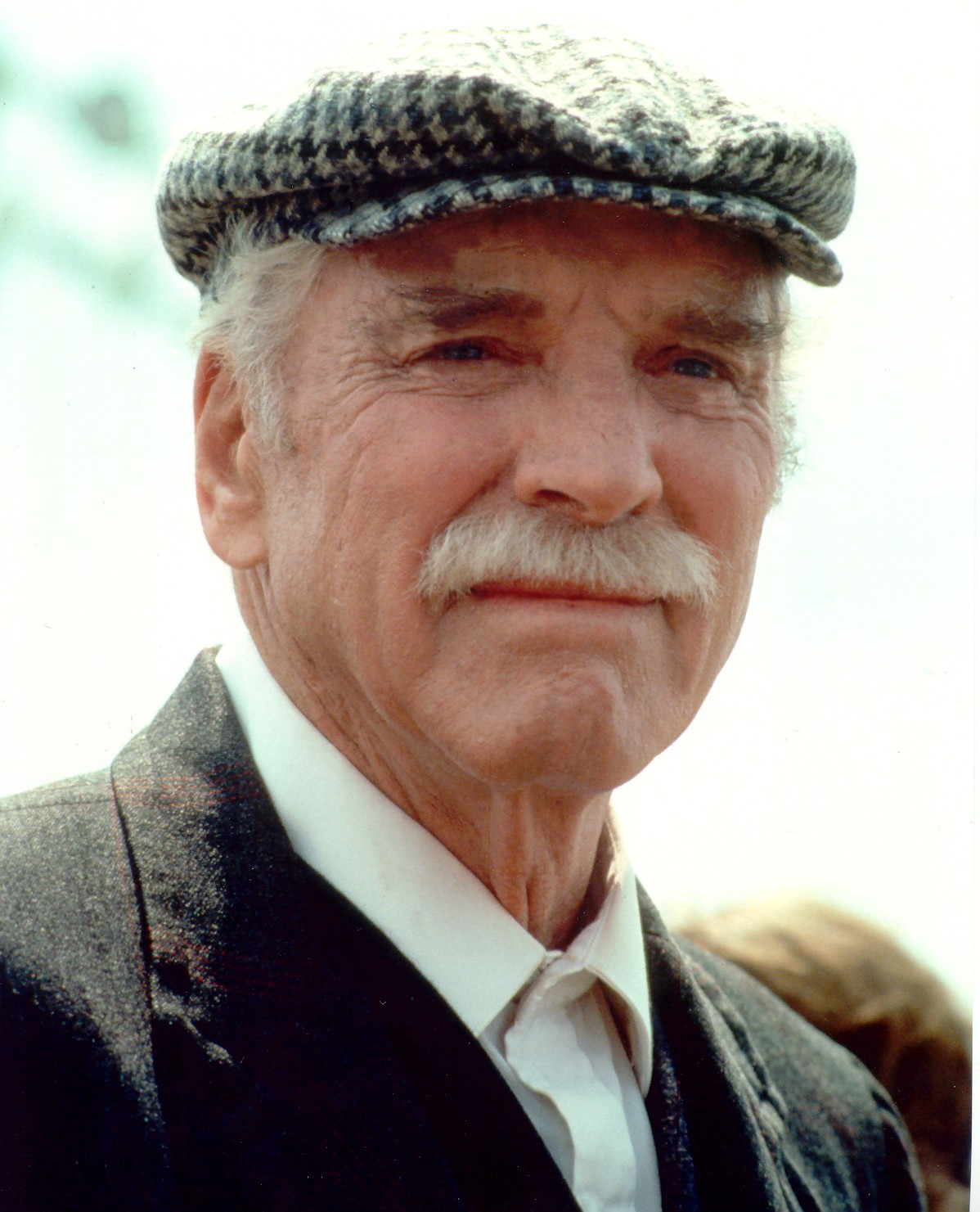

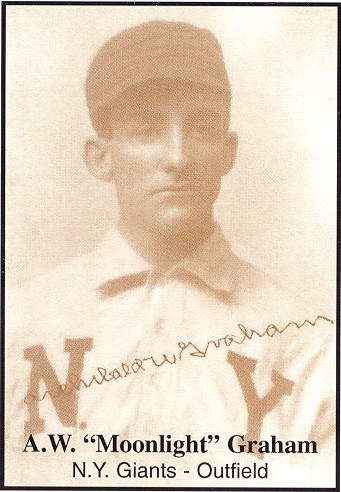

Archibald Graham, called "Moonlight" Graham when he played one inning for the New York Giants in 1905 (near right; the film moves it up to 1922), played one inning and never got to bat. Quitting baseball, he became the beloved "Doc" Graham (near right) of Chisholm, Minnesota, where he was every bit the town doctor and hero Burt Lancaster (far right) portrayed him as.

Old Doc had one great wish: that he could have gotten to bat just once in the major leagues...to face down a big league pitcher...to stare him down and...just as he goes into his windup...wink...make him think you know something he doesn’t...to squint into the sun and the sky so blue it hurts your eyes just to look at it...to feel the tingle in your hands when the bat connects with the ball...to round the bases...stretch a double into a triple...to dive into third and wrap your arms around the bag.

"Is there enough magic out there in the moonlight," old Doc asks, "to make this dream come true?" There is! Doc gets the chance at bat that he missed in his youth. He gets to bat in the big leagues, and the glow of ultimate joy that lights up his face is worth the price of the movie alone.

Finally, Ray's father, John Kinsella, gets to catch in the major leagues, which in life he never got to do. More than once the question is asked: "Is this heaven?" And Ray has to respond, "No, it's Iowa."

At last, the boy who once refused to "have a catch" with his dad has a catch with his dad.

James Earl Jones: "In Field of Dreams, Kevin's character strives to reconcile with his father. In his succeeding, we're taught that second chances are possible." If you can watch the scene of Ray meeting his long-dead father again without using up a box of Kleenex, well, you need a heart transplant. "Is this heaven?" John Kinsella asks, and his son tells him, "It's Iowa."

John seems disappointed. "I could have sworn it was heaven," he says, and now it's Ray's turn to ask, "Is there a heaven?" And John answers with certainty, "Oh, yeah! It's the place dreams come true." Ray looks around ~ at the field he has just built, at the deepening shadows of dusk, at his wife and daughter sitting on the porch of their home ~ and smiles. "Maybe this is heaven," he says.

You can visit the movie set in Dyersville, as my wife and I did on a

splendid September afternoon. It will be there as long as people come, and to

this day they still come: 7,000 in 1988, the year Field of Dreams was

released; more than 200,000 in 1994; about 50,000 last year. On any given day,

the tourists will outnumber the population of the town. They come from every

state, and from many foreign countries, in groups or by themselves, in the

spring, summer, fall and winter. The farmhouse (top right) sits on top of the

little hill, the baseball diamond in the middle of the cornfield, jointly

owned and maintained by the same people who owned them then: Don and Becky

Lansing, who own the house, most of the diamond, and right field; and Rita and

the late Al Ameskamp, who own most of the cornfield (which the wife emerges

from at far right), most of center field, and third base. They remain pretty

much unchanged from when the movie was filmed 13 years ago, though the

Ameskamps have sought to commercialize the site more with a 1.6-mile cutaway

of Shoeless Joe carved out of the cornfield for people to walk through, as

well as batting cages, expansion of the gift shop, and a series of

motivational seminars.

You can visit the movie set in Dyersville, as my wife and I did on a

splendid September afternoon. It will be there as long as people come, and to

this day they still come: 7,000 in 1988, the year Field of Dreams was

released; more than 200,000 in 1994; about 50,000 last year. On any given day,

the tourists will outnumber the population of the town. They come from every

state, and from many foreign countries, in groups or by themselves, in the

spring, summer, fall and winter. The farmhouse (top right) sits on top of the

little hill, the baseball diamond in the middle of the cornfield, jointly

owned and maintained by the same people who owned them then: Don and Becky

Lansing, who own the house, most of the diamond, and right field; and Rita and

the late Al Ameskamp, who own most of the cornfield (which the wife emerges

from at far right), most of center field, and third base. They remain pretty

much unchanged from when the movie was filmed 13 years ago, though the

Ameskamps have sought to commercialize the site more with a 1.6-mile cutaway

of Shoeless Joe carved out of the cornfield for people to walk through, as

well as batting cages, expansion of the gift shop, and a series of

motivational seminars.As it is, there is the gift shop and a Visitors’ Center. But it isn't the farmhouse, the gift shop, or the field itself, or even the cutaway of Shoeless Joe, for which they come. "Reconciliation is a major reason why people come," explains Dyersville Chamber of Commerce Executive Director Jacque Rahe. "A couple of years ago, I remember two brothers met at the field. They hadn't seen each other or spoken to each other in over 30 years, but they met by chance at the Field of Dreams and they reconciled their differences."

The site reaches right into people's hearts, and Rahe adds that visitors "project the story of the film onto their own lives." Family members often photograph each other walking out of the corn and onto the playing field. Jacque's husband Keith was one of the ghost players in the film. "It's an amazing example of life imitating art," Rahe says.

People come here to fantasize, Al Ameskamp comments. You’ll see a constant game going on, strangers playing together from all over the world.

Becky Lansing adds, Some come for the spirituality. Some for fulfilled and unfulfilled dreams. This is a vortex for all that is good.

Every Labor Day weekend there is a big to-do featuring a charity baseball game between the Upper Deck Company and Hollywood celebrities. More than 30,000 in 1994 came to this event alone. And, speaking of ghosts of the past: Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, Joe Pepitone, Reggie Jackson, Sadaharu Oh, Jose Cardenal, Bob Feller and Jimmy Piersall have all appeared there.

Admission is free, but donations are welcome. You can buy souvenirs and sit on the bleachers; and, on the last Sunday of every month, you can watch the ghosts of players long dead walk back out of the corn stalks to play this wondrous game. Beneath the soothing rays of the Iowa sun you can dip yourselves in magic waters and brush the memories from your face; and, if you close your eyes and open your hearts, you might hear Shoeless Joe Jackson or John Kinsella ask, "Is this heaven?"

"No," you'll hear yourself say, "it's Iowa."

And then, suddenly, you'll know in your heart, where the game of baseball is really played, that maybe this is heaven after all.

Unpublished work © 2006 Henry Zecher